In her new memoir, ‘America’s foremost nutrition warrior’ shares her life’s work influencing nutrition policy behind the scenes, and how she overcame the barriers and biases facing the women of her generation to find her purpose after 50.

In her new memoir, ‘America’s foremost nutrition warrior’ shares her life’s work influencing nutrition policy behind the scenes, and how she overcame the barriers and biases facing the women of her generation to find her purpose after 50.

September 21, 2022

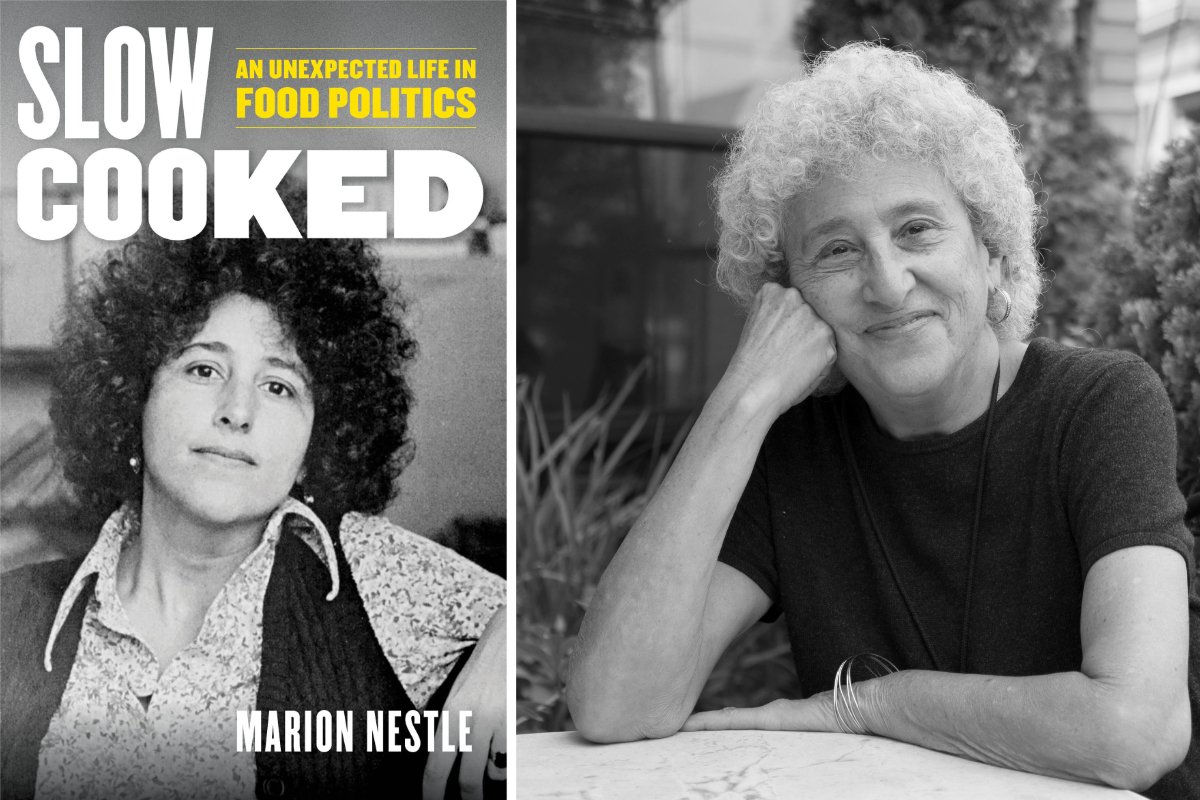

Marion Nestle photo credit: Bill Hayes.

For nearly half a century, Marion Nestle has been teaching and writing about the politics of what we eat. The author of 14 books, her latest, Slow Cooked: An Unexpected Life in Food Politics, is a memoir—and a decidedly personal story of becoming the individual experts have called “one of the nation’s smartest and most influential authorities on nutrition and food policy,” the “leading guide in intelligent, unbiased, independent advice on eating,” and “America’s foremost nutrition warrior.” (My favorite: “food visionary badass.”)

In the book, Nestle recounts a challenging childhood crisscrossing the country and then quitting college to get married at 19. Ten years later, divorced with two children, she decided to resume her studies. She later became a professor in biology and nutrition science at U.C. San Francisco, served as a senior nutrition policy adviser for the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and became the chair of the Department of Home Economics and Nutrition at New York University (NYU) in 1988. But it was her 2002 book, Food Politics, that marked a turning point in her life, when she was 66.

Nestle writes, “I knew early on that I loved food and wanted to study it. I wish I had been able to pursue this goal right from the start. Instead, I did what I could manage at the time between raising kids and following my husband[s] decisions, I tried to make the best of my circumstances.” Until she was hired by NYU, she recalls, “I had never thought about what kind of work I might want to do if I had choices.” Once she did have the opportunity to blaze a career trail as a critical analyst of the food industry, however, she did so with gusto.

Civil Eats spoke to Nestle (who also sits on Civil Eats’ advisory board) the day before her 86th birthday about her impressive career in food politics and nutrition science, her experiences influencing nutrition policy behind the scenes, and how she overcame the barriers and biases facing the women of her generation to find her life’s purpose after 50.

You write about so many obstacles and challenges, both as a woman, but also within the bureaucracies you faced. How you were able to manage so many instances of blatant discrimination?

Marion Nestle in the lab, photographed for the Brandeis course catalog. (Photo credit: Jessie YuChen)

It just never occurred to me that there was anything personal about the discrimination that I faced. I assumed that it was normal. Women didn’t have options; you were expected to get married and have children and do that as quickly as possible. If you worked at all, it was to support your husband’s career. I had no role models. I didn’t know any women who lived on their own. I was trying desperately hard to socially conform. And then I got married after my sophomore year in college. I look back on it and it doesn’t seem like it was the brightest thing to do. Although I have two lovely children as a result, that’s what everybody did.

I have no memory from those years of anybody saying, “You really ought to try to do more, and you can do more,” until I was advised to go to graduate school by a friend who said, “You’ve got to just do this.” And then I went to graduate school in molecular biology because I knew I could get a job and, even then, I faced so many obstacles.

Your recollection of the politics of the 1988 Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health, and your involvement with it, was fascinating. The report focused on reducing people’s intake of fat, which became a major emphasis for food companies to manipulate ingredients and food products—i.e., the SnackWell effect, which resulted in a whole array of nonfat foods that were loaded with sugars.

Well, I really believed in the report. It was designed to settle the science—to the extent that the science could be settled—and provide advice for people about what was healthy to eat. And it came out of an office that had a lot of experience with big reports.

I had just written a book about everything medical students needed to know about nutrition, so I was the perfect person to bring in for this report. On the first day, I was told that no matter what the research showed, the report could never say eat less of any American food product, because whoever made that food product, particularly the meat industry, would bring in the Department of Agriculture, and they would stop the report from ever being published. And they weren’t joking. This was not paranoia, it was reality.

I spent probably a third of the time trying to manage an Undersecretary at the Department of Agriculture, who was on my case all the time about what that report was going to say about meat. They were going to use saturated fat as a euphemism for meat, and the meat industry could live with that because nobody understands what saturated fat is. It was a very difficult experience. And I just kept persisting—it was one of those “she persisted” experiences. I did most of the writing of that report, endless rewriting of other people’s work. And somehow, in the end, I got away with it, except for the executive summary, which was the one part that still makes me cringe. I didn’t have anything to do with that.

Let’s talk about the 1991 USDA food pyramid. You were involved in many behind-the-scenes machinations. At one point, you write that you felt like “Bob Woodward talking to Deep Throat.”

In 1991, the Department of Agriculture released a new food guide pyramid which had been under research for 12 years. It was totally finished and ready to be printed. And then somebody wrote an article about it in The Washington Post and said that it was going to have meat at the top, in the part of the pyramid that you’re supposed to eat less of. And that was a radical new approach for the Department of Agriculture. The article came out on the Saturday when the cattle National Cattlemen Association was meeting in Washington. They read the article and scheduled a meeting with the brand-new Secretary of Agriculture on the following Monday, and said, “You can’t do that.” And that new Secretary didn’t know anything about the history of it. So, he just said, “Oh, this hadn’t been tested on low-income women and children.” And he withdrew it saying that was the reason.

“I was told that no matter what the research showed, the report could never say eat less of any American food product, because whoever made that food product, particularly the meat industry, would bring in the Department of Agriculture, and they would stop the report from ever being published.”

I was interviewed by the Post, and said something like, “Once again, the cattlemen are exercising their muscle and interfering with dietary guidance policy.” And I got a call that very night from someone I knew at the Department of Agriculture, who said, “I have documents that will prove that the Secretary of Agriculture is lying [about why it was withdrawn]. We’re not allowed to talk to the press. Do you think you could get these documents to the press?”

And I could do that pretty easily. So, pretty soon, all this stuff started arriving in plain brown, unmarked envelopes, posted from hotels and completely neutral places. And I called Marian Burros at The New York Times and said, “You want to see this stuff?” She said, “Do I ever.” And she started writing about it, and then everybody else started writing about it. I eventually put together a press kit of the relevant documents, the Xerox copies of the original pyramid that was withdrawn, other things that showed that everything had gone through clearances, had been researched and focus group tested it, that it had in fact been completely cleared through every level of the Department of Agriculture.

Eventually, Marian got somebody to tell her enough so that she pieced together what the Department of Agriculture was planning to do, she published it, and that forced their hand. A year later, they released the pyramid that was much the same as the original except for a few details meant to appease critics in the meat industry. And it lasted until the 2010 My Plate [guidelines], which replaced it.

I always thought it was a really good design. And it had been researched much more heavily than any other food guide that I’m aware of. My Plate was not researched at all, as far as I know. Or if it was researched, [that research] was never published.

How did you expand on the existing curriculum at NYU when you started the food studies program in 1996? You write, “We knew we were breaking new ground with food studies but we had no idea we would be starting a movement.”

That was a big high point. We went from the concept to the actual program in less than a year. I spent the whole first year trying to explain what food studies was, with this completely blank look on people’s faces. I remember talking to the provost at NYU one night at dinner, and I tried to explain that food is a business that brings in trillions of dollars a year. Everybody eats. It’s enormously influential in people’s health. It affects climate change. It’s related to agriculture, to farm bills, to government, to lobbying, to politics, to sociology, to anthropology, and anything you could think of. I’d waited all my life for this program.

“Food is a business that brings in trillions of dollars a year. Everybody eats. It’s enormously influential in people’s health. It’s related to agriculture, to to government, to anthropology, to anything you could think of. I’d waited all my life for this program.”

There was a program in gastronomy at Boston University at the time. And there was an anthropology program at the University of Pennsylvania in food. Now, I don’t think you can go to a university in the United States, or in most countries in the world, and not find courses about food in society, food and culture, food and climate change. I mean, they’re everywhere. There are whole schools and universities devoted to it. At this point, there are more than 60 listed on the society websites that deal with this. There are journals, series of books and encyclopedias, and everybody’s writing about food. I say bring it on!

How did writing Food Politics change your life?

I had three goals in writing it. I never wanted to go to another meeting about childhood obesity and hear people talk about how we have to teach mothers how to feed their kids better. I wanted to hear people say, “How are we going to stop food companies from marketing junk foods to our kids?” At the time, the American Dietetic Association published handouts on specific food topics that were sponsored by food companies with a vested interest in what those handouts said, and I also wanted the Dietetic Association to stop doing that. I mean, they had Monsanto paying for a handout on genetically modified foods and artificial sweetener companies doing handouts on artificial sweeteners and sugar companies doing handouts on sugar. I just thought that didn’t work. And I wanted better speaking invitations.

You have to be careful what you ask for, because I eventually I got all of those things. I mean, certainly the idea that food companies are marketing to kids is common knowledge now and everybody knows it and is worrying about it. And the Dietetic Association eventually stopped doing those things. And oh, my goodness, did I get better speaking invitations, I mean, more than I could possibly handle. It put me in a position of being able to do more writing, which I love.

You love to write books, research, and talk to people. But this is a very personal book. How are you feeling about talking about yourself?

I grew up in the 1950s and yet I have tried very hard to stay current and move with the changes. And the changes have been enormous. The things I cared about at the beginning of my career are things I still care about very deeply. I want everybody to have access to healthy, affordable diets that are sustainable. I want to stop the food industry from trying to get everybody to eat unhealthily. I understand that they have shareholders to please. But that cannot be the only reason for allowing them to do what they want to do when it is so bad for public health and for the environment. And to the extent that more and more people understand how important those two issues are, that’s my rationale for having written this book.

“The things I cared about at the beginning of my career are things I still care about very deeply. I want everybody to have access to healthy, affordable diets that are sustainable. I want to stop the food industry from trying to get everybody to eat unhealthily.”

What gives you hope and what keeps you going?

I’m privileged to teach young people and they are faced with a world that is much more difficult than the one I faced. People today coming of age now are facing a world that’s really difficult. Maybe five years ago, I could not give a lecture and use the word “capitalism” without turning people off and scaring people. Now, if I don’t, somebody says, “Why aren’t you talking about capitalism?” When I started out writing Food Politics, the first question that I got asked is, “What does food have to do with politics?” Now, everybody gets the politics.

During the pandemic, you saw what happened in the meatpacking industry, with food assistance programs, with supply chains. When people who worked in grocery stores became public heroes. That’s food politics. Everybody could see it. And I think young people get it loud and clear. They understand why capitalism isn’t working for them. They can see the inequities and the unfairness of it and they want to do something about it. That gives me hope!

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Slow Cooked debuts October 4, 2022; to receive a 30 percent discount, visit the U.C. Press website and use code 21W2240 at checkout.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.