New research from Columbia University has found that the arid-humid boundary at the 100th Meridian has shifted 140 miles, expanding the drier lands to the east with significant implications for agriculture.

New research from Columbia University has found that the arid-humid boundary at the 100th Meridian has shifted 140 miles, expanding the drier lands to the east with significant implications for agriculture.

April 25, 2018

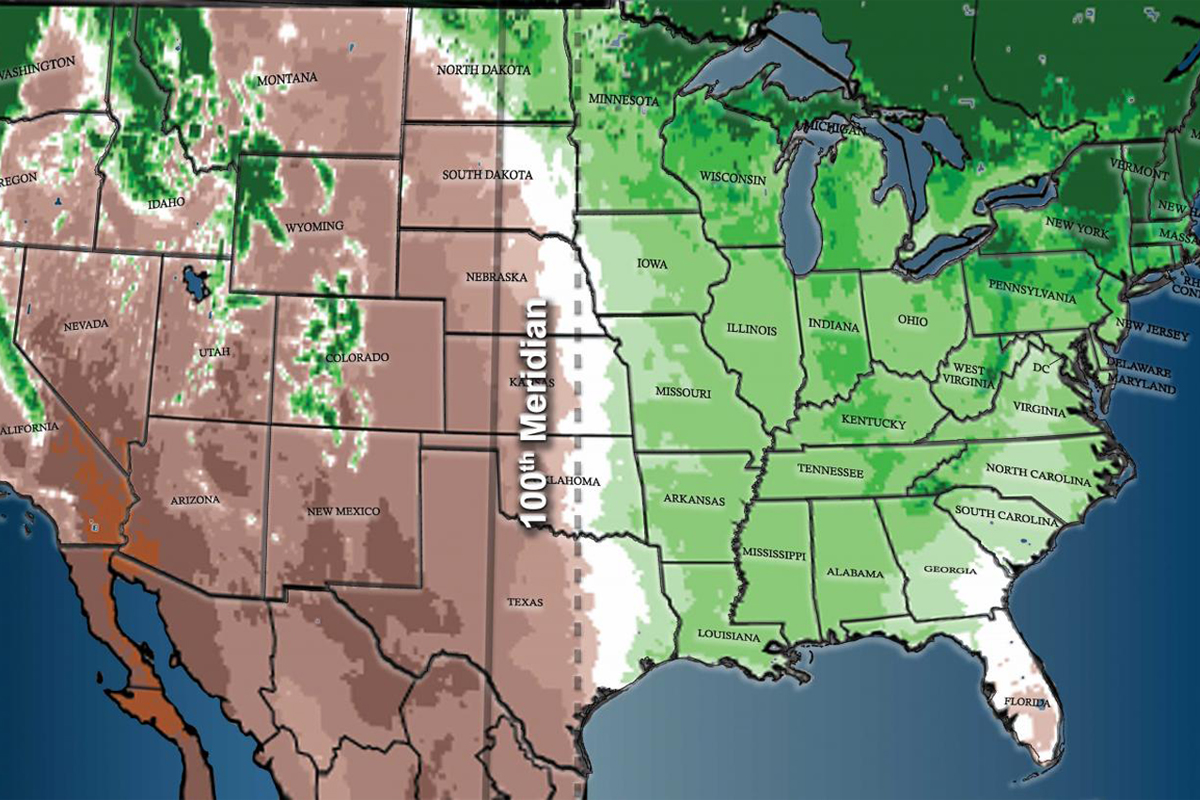

In 1878, noted geologist and explorer John Wesley Powell observed that the 100th Meridian, the longitudinal line that slices north-to-south through the Dakotas, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, represented a distinct boundary between the humid Eastern United States and the arid western plains. The invisible but distinct climactic divide, Powell said, should influence how people on either side settle, manage, and farm the land.

Nearly a century and a half later, a Columbia University study published in the April issue of the journal Earth Interactions re-examined the boundary line—and presented two central findings: first, that the boundary is real, and second, that climate change is causing it to migrate east, expanding the dry part of the country.

Despite the fact that many farmers still don’t acknowledge the link between human activity and climate change, only 18 states have climate mitigation plans in place, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has removed numerous climate-related documents from its own website, the resulting changes to agriculture will likely be hard to deny.

“There’s no point in sticking your head into the sand—or into the tilled earth—about this: these changes are going to be happening,” said climate scientist Dr. Richard Seager of Columbia’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory and the study’s lead author.

“In any decision-making, it’s worth thinking that conditions are going to change and it’s going to require some adjustment in how the land is used agriculturally. What’s the best thing to do that will minimize destruction and suffering that will occur?”

Though most contemporary Americans have probably never heard of the 100th Meridian, it’s an environmental reality. In fact, Seager’s team confirmed its existence by examining east-west differences in vegetation, precipitation, temperatures, and atmospheric circulation, as well as human approaches to settlement and agriculture.

East of the line, the researchers found, the land receives moisture-rich air blowing off of the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico as well as precipitation from Atlantic winter storms. As a result, farmers in the more populated and developed eastern plains tend to grow moisture-loving corn and maintain pastures of rich, tall grass.

Because the Rocky Mountains rake off moisture from the Pacific Ocean before it reaches the western side of the country’s interior, and breezes from the Atlantic and Gulf stop short and curve eastward, respectively, the land west of the divide is much warmer and drier. In this region, where human population and infrastructure is sparse, farmers tend to raise cattle on unimproved rangeland and grow aridity-resistant wheat. To stay profitable in the harsher conditions, farms west of the 100th Meridian tend to be larger, and there are fewer of them.

“Even if there were no humans doing anything, you would still be able to find that line on the landscape,” Seager said. “You would still be able to see it from an airplane flying over, or from space.” The fact that humans are acting on the environment, he said, only adds to the natural variability.

In addition to confirming the line’s existence, the team determined that because of climate change, the humid/arid dividing line once located at the 100th Meridian has shifted to the 98th Meridian, about 140 miles east, since 1979. The change was caused by rising temperatures from fossil fuel-generated greenhouse gas emissions. Higher temperatures caused more soil moisture to evaporate, and shifting wind patterns have decreased precipitation in the southwest. Climate models adjusted for the particular topography of the American West project that the line will continue its march toward the Atlantic, likely moving an additional two to three longitudinal degrees by the end of the century.

Under the new, drier environmental conditions, Seager predicts that more land will become suited for rangelands and wheat and less land will be suited for pasturelands, corn, soybeans, and other water-loving crops. He expects that farmers in newly arid territory will have to decide whether to change what they grow or irrigate their crops. He also predicts a shift to fewer and larger farms.

And that’s not the only climate-related bad news for farmers. A recent BMI Research report also forecasts more frequent droughts, flooding, and storms in the coming decades and predicts that as the climate changes, agriculture will shift from being labor- to capital-intensive. With temperatures rising and water growing scarce, stricter agricultural regulations will likely require that farmers adopt more environmentally friendly equipment and methods, the report’s authors predicts. Farmers will likely turn to technology to help them increase yields and solve the problems that arise, and precision ag tech companies will likely profit at the expense of growers.

When Powell first introduced the idea of the 100th Meridian boundary in the late 1800s, he argued before Congress that European settlers migrating west should consider the constraints imposed by the land’s aridity. Though settlers did in fact face the environmental realities Powell described, his ideas about thoughtful and sustainable resource management did not gain traction with the politicians of the time, who did not want to acknowledge environmental limits to western expansion. (“It was an early version of ‘An Inconvenient Truth,’” Seager noted.)

“Powell was very wise in saying the way you settle and develop this land should be scientifically informed and aware of the environment,” Seager said. “Had that advice been taken, we might have ended up from a very different West than the one we have now.

“As the climate is changing due to human activity,” Seager added, “[Powell’s] wisdom is even more appropriate now.”

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 24, 2024

September 18, 2024

If tiny krill can mix the ocean, we can circulate the soil. Group momentum is the problem, AND the solution.

Not nearly as favorable for those more southerly central plans states like Oklahoma, Kansas, Nebraska. You know as described in the article.