In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

January 26, 2021

As an attorney working on school desegregation cases in the South, GeDá Jones Herbert is intimately familiar with inequities and discrimination that Black families face on a regular basis. And when schools began shutting down in-person instruction last March due to the pandemic, she heard from many of her clients.

“We knew that [the pandemic] was going to have a huge impact on the lives of our clients and students across the country,” said Herbert, who is based in New Orleans and works primarily on cases in Louisiana and Alabama. “As we were assessing the closures, the things we were really looking at were access to distance learning . . . and food and nutrition.”

Her team at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund (LDF) zeroed in specifically on the connection between meal access and race. The education lawyers knew many students from low-income families depended on school meals for adequate nutrition. In 2019, more than 29 million children ate free and reduced-price school lunches daily. In the communities LDF was working in, they also knew that a disproportionate number of those students were Black.

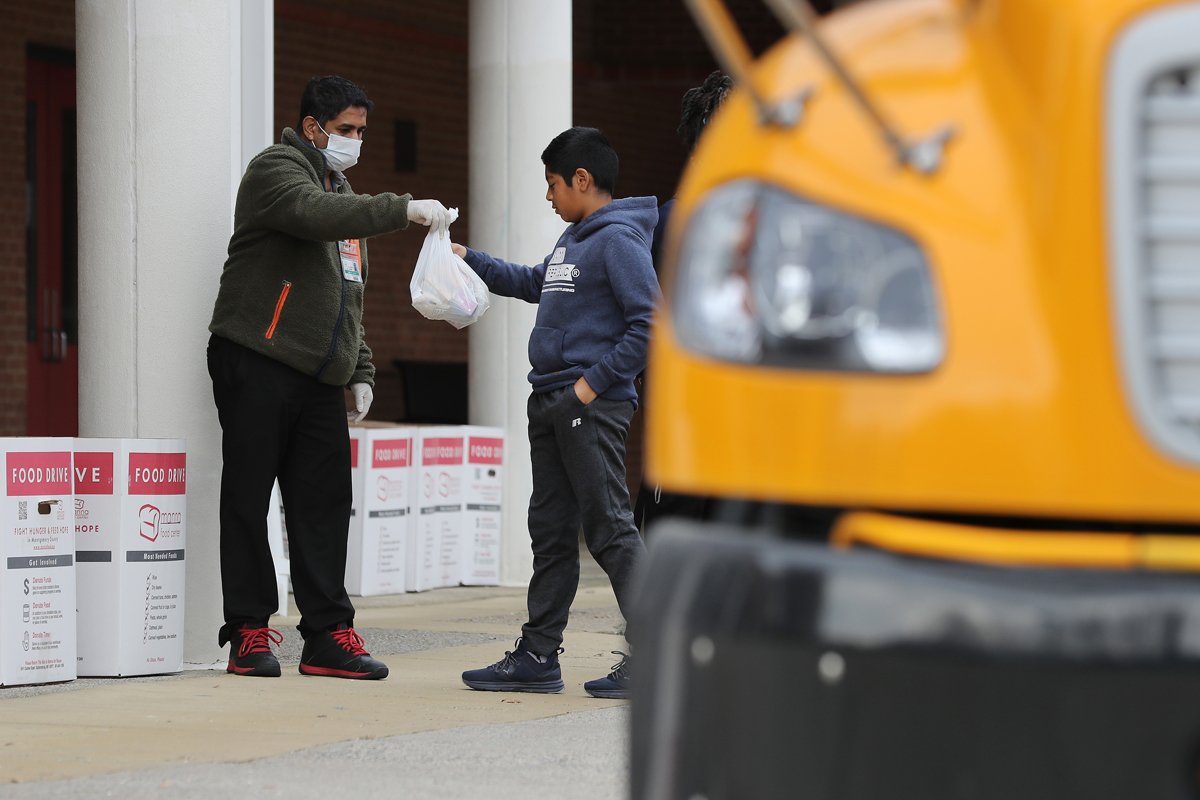

Once COVID-19 began its spread early last year, school nutrition departments across the country began scrambling to continue serving meals in various ways. After waivers from the federal government allowed them to make changes like packaging meals to go, some districts set up pick-up sites, and others used bus drivers to deliver meals. But many districts began going broke in the process, and others faced COVID outbreaks. In response, some districts limited pick-up site operation to just a few hours a week, and others stopped serving meals altogether.

Herbert and her team argued that several districts that ceased meal service were violating civil rights laws, because such a high proportion of students eating the subsidized meals were Black. Even in places where meals were offered, limitations like site location and pick-up times prevented many Black families from accessing them.

LDF sent letters to the governors of Louisiana and Alabama detailing their legal arguments and sharing what they were hearing from clients. “A child without access to transportation by car in the Four Corners neighborhood in St. Mary Parish [southwest of New Orleans on the Gulf of Mexico] would have had to walk four hours each way to get to the nearest ‘Grab n Go’ site, each of which was open for a mere hour and a half,” one letter read. “Even after the district eventually added a Baldwin site, children in the Four Corners neighborhood still would have had to walk two hours each way to pick up their breakfast and lunch.”

In Leeds, Alabama, schools stopped providing meals entirely on April 2. LDF sued the district there, forcing it to restart meal service. LDF’s efforts caught the attention of researchers at Columbia, Harvard, and the University of North Carolina. They began working on several projects that looked at whether access to school meals during the pandemic was affected by race.

The situation gained the attention of several members of Congress as well. In June, Representative Bobby Scott (D-Virginia), chairman of the Committee On Education and Labor, sent a letter to former Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue. “I am concerned that during this pandemic, many Black and other children of color are left hungry due to inadequate access to school meals,” he wrote, noting a dire statistic: During March and April, the rate of food insecurity for Black households was double that of white households.

Since then, districts across the country—including those LDF is monitoring—have gotten better at streamlining pandemic meal services, giving more students access to food. And schools are back in session in some areas. But racial discrepancies still exist.

In December, the Urban Institute reported 40 percent of Black families with school-age children were food insecure in September, compared to 15 percent of white families. Meanwhile, nearly two thirds of all families reported that their children were not receiving meals from schools. “These data suggest that a significant portion of vulnerable children may not be benefiting from school-based nutrition resources amid the shifting mix of virtual and hybrid instruction,” the report noted.

And while school meal access may not be as stark an issue as it was just months ago, Herbert and other experts say questions of how to guarantee equitable access to school meals—and whether the current system does enough to consider race—are more pressing than ever.

“Just because a system has been put in place and people are maintaining it for now doesn’t mean that the problem is solved,” she said. “This is going to continue to be an issue, so we really have to develop some longer-term solutions.”

When schools shut down, researchers around the country who focus on school meal programs began sharing resources and chatting online about what they were seeing. Julia McCarthy is the interim deputy director of the Laurie M. Tisch Center for Food, Education & Policy at Columbia University. She formed a research team with Caroline Glagola Dunn at Harvard and Jared McGuirt at the University of North Carolina Greensboro to begin studying school meal access across the country.

When she saw LDF’s letter to the governor of Louisiana, McCarthy was shocked. To help document evidence of possible disparities in southern Louisiana districts, McCarthy, Dunn, and McGuirt used U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and district data to visually depict where meal pick-up sites were located in relation to the percentage of the neighborhood population that was Black.

Based on those maps, “It was pretty consistent across the board that sites were more conveniently located for white families,” Herbert said. She anticipated that the problem would be exacerbated by the fact that based on the most recent data, 17 percent of Black residents in Louisiana don’t have access to a car, compared to 5 percent of white residents.

“In the westernmost part of St. Mary Parish, the census block tract there is 72 to 88 percent Black. There wasn’t a single meal distribution site there,” McCarthy said.

St. John Parish, about 30 miles northwest of New Orleans, is an area known for a history of environmental racism, with Black communities bearing the brunt of toxic air pollution from chemical plants and oil refineries. The parish has the highest risk of cancer due to air pollution in the entire country.

A March 2020 map of meal sites in the parish revealed just four pickup locations, three of which were on one side of the Mississippi River. “There’s not a single bridge in that parish,” McCarthy said. “[For] all of the families on the south side of the Mississippi, there’s only that one spot.”

In neighboring St. James Parish, which covers 258 square miles, the researchers identified just four meal sites. On March 22, the school district there stopped serving meals altogether. “It’s been like we are a parish that’s been left behind,” said Rhoda Johnson, an LDF client and grandmother to children in St. James Parish schools. “They just stopped feeding the children.”

Both McCarthy of Columbia and Herbert of LDF acknowledge the challenges schools were facing to produce meals at all and keep staff safe during the pandemic. And they said that while placing meal sites without considering the needs of Black families was likely not intentional, it pointed to the deep-rooted, systemic nature of racism in the U.S.

“[Unequal access to meals] has its roots in our history of segregation in America,” Herbert said. “The whole premise behind Brown v. Board of Education was that resources follow white communities, and if Black students were ever going to be able to have the resources they deserved, white communities were going to have to share.”

That conclusion squares with what Birmingham resident Celida Soto Garcia has observed in Alabama since the start of the pandemic. Garcia lives in Birmingham and works on hunger advocacy for Alabama Arise, a nonprofit dedicated to the interests of the state’s low-income residents. Since last March, she has focused entirely on what she called “the conundrum of getting meals to families.”

Unlike in some parts of Alabama, Birmingham had a highly developed plan for getting meals to students, Garcia said. But even there, barriers for Black families existed. “We have a 74 percent Black population here, and a lot of Black students have elderly caregivers,” she said. “They don’t have cars.”

Things are much worse in rural areas like Alabama’s Black Belt, an area named for its rich agricultural soil. It is also highly populated with Black families, many of whom are descendants of enslaved people who worked on cotton plantations there. “It’s highly rural and is really disconnected from access to food, access to health care,” Garcia said. “In areas like Sumter, Perry, and Macon counties, they’re literally scrambling to come up with solutions to deliver school meals.”

Garcia said the schools are doing everything they can, but needed resources rarely reach the communities. “That leaves the question: ‘Why?’ Every time they say, ‘Well, it’s a matter of getting the federal funding down here.’ Okay, why isn’t it here? You have to dig deeper and keep asking why,” she said. Often, the answer has to do with a history of discrimination against people of color.

And that extends beyond Black families. Celsa Stallworth lives in Leeds, Alabama—where LDF sued the school district after it stopped serving meals last April—and has an 11-year-old in school there. Stallworth works for a local nonprofit that supports Hispanic immigrant families, and she said that community was also disproportionately affected by the suspension of meal service.

“During that particular time, I was delivering food and reaching out to different family members that were having problems with [getting] groceries and hot meals,” said Stallworth. “We stepped up our efforts when I was told that they won’t have access to the meals at school.”

Many immigrants she knew were out of work due to restaurant closures. And, most significantly, most aid programs in the area require documentation of citizenship to access benefits. Even when they don’t, she said, misinformation abounds and immigrant families fear asking for help. “So, the resources are extremely limited,” she said.

In the early days of the pandemic, McCarthy, Dunn, and McGuirt worked on a larger research project that looked at how four of the country’s largest urban school districts—in Houston, Los Angeles, Chicago, and New York City—implemented meal distribution programs.

That study, published in September, found that the cities did tend to prioritize placing sites in neighborhoods with more families of color. All four districts placed significantly more meal sites in high-poverty areas. All except Chicago had significantly more sites in neighborhoods with larger minority populations.

Another national analysis, also out of the Tisch Center, found the vast majority of rural school districts in the sample continued to provide meals, but the frequency, distribution model, and communication about meal service varied greatly from district to district.

That points to the fact that that districts need more guidance when creating emergency food distribution plans, said McCarthy.

“When we did the rural case study, when we did our urban case study, when we looked at these maps . . . what it all really demonstrated was that these districts were struggling to figure out how to best serve kids at a time when need was highest,” she said. “They really didn’t have any best practices or guidelines in place. There was no federal leadership telling them to consider factors like racial access, access to transportation, etc.”

Moving forward, McCarthy hopes to see the USDA develop a school meal distribution plan for emergencies, which incorporates all of the data and learning that will come out of this time.

Over the long-term, she’d also like to see the agency start tracking meal service participation based on race. “We don’t actually know if the percentage of eligible Black students is equal to the percentage of participating Black students, simply because we don’t report school meal data by race,” she explained.

That kind of data could inform future efforts to ensure equitable meal access. For example, many advocacy organizations are currently pushing for the USDA to permanently offer universal school meals instead of requiring eligible families to apply. Data on whether or not BIPOC students across the country are receiving the meals they’re eligible for would be especially relevant to that discussion.

While federal nutrition policy is not what LDF focuses on, Herbert said data is always a good thing for lawyers looking for inequality.

For now, the districts she works in are operating meal service programs for students still at home, and she is focused on monitoring those efforts to make sure they “don’t fall back through the cracks.”

She’s also monitoring whether families are able to access benefits from the Pandemic Electronic Benefit Transfer (P-EBT), a program launched in March 2020 that helps low-income families buy their own food, rather than needing to rely on school meals.

Last week, President Biden directed the USDA to increase P-EBT benefits by 15 percent. In addition to recent increases in SNAP benefits authorized by Congress’ last COVID relief bill, he also directed the USDA to get emergency SNAP allotments to the lowest-income households.

As the new administration continues to tackle rising food insecurity, it’s important to remember that vulnerable children, overall, will benefit from equitable access to school meals, Herbert said.

“If these Black students aren’t getting these meals, that also means that there are Latino students who aren’t getting meals,” she said. “There are maybe white children from less affluent areas who aren’t getting meals. We’re always going to unapologetically fight for Black communities. [And] when we do, we really support all communities.”

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 24, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.