Maria Finn discusses her new cookbook, her approach to what she calls ecosystem-based living and eating, and why foraging can be controversial.

Maria Finn discusses her new cookbook, her approach to what she calls ecosystem-based living and eating, and why foraging can be controversial.

April 9, 2024

Like many food professionals, Maria Finn lost her job in 2020 after COVID shut down the world.

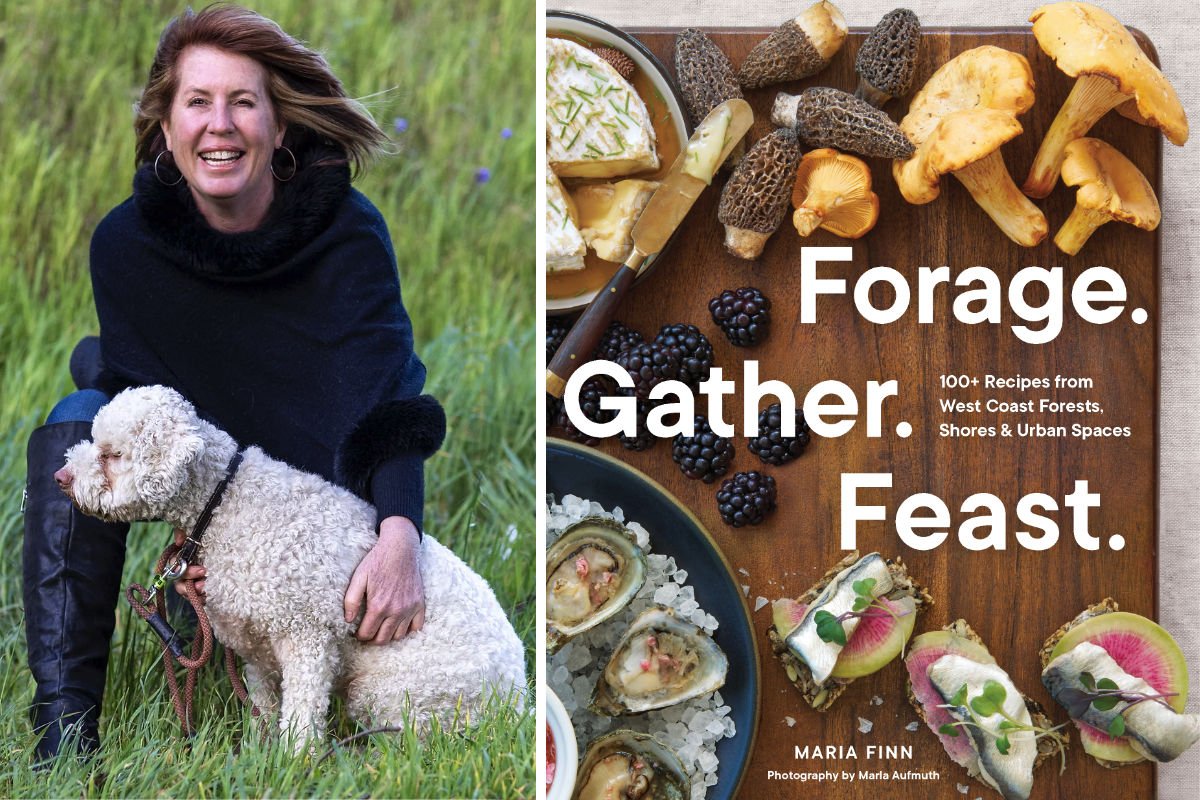

She was working as a chef in residence at Stochastic Labs, an incubator in Berkeley that brings together engineers, artists, and scientists to collaborate on and discuss the future of technology. Finn had been a forager for years. After COVID hit, Finn adopted a truffle dog named Flora Jayne and launched Flora & Fungi Adventures to teach people how to cook and forage for wild foods such as mushrooms, seaweed, and Dungeness crab.

Her adventures culminated in a book, Forage. Gather. Feast. 100+ Recipes from West Coast Forests, Shores, and Urban Spaces, which hits bookstores today.

One of the book’s goals is to inspire people to develop deeper relationships with their local ecosystems so they’ll be motivated to protect those places.

“When people really care about food, whether it’s a farmer, a fisherman, or a chef, they have a relationship with it.”

“I’m not encouraging everyone to go live off the land, but it’s a really great way to get outside and get connected to the cycles of nature,” Finn says. “It can be a magical experience.”

Everyone is born a forager, says Finn, who has also worked as a journalist, author, and speaker. “Little kids love it, then we [grow up], and it doesn’t occur to us. Even if you’re looking at trees laden with fruit, it doesn’t always occur to you that you could go pick that and eat it.”

But once people begin foraging, Finn says it becomes a new way of viewing the natural world, inspiring curiosity and an appreciation for the subtlety of the seasons.

Civil Eats spoke to Finn about her new cookbook, her approach to what she calls ecosystem-based living and eating, and why foraging can be controversial.

I love how you write about being a deckhand and cook on an all-female commercial salmon fishing boat in Alaska. You also write about learning how to find wild spinach from a Yup’ik woman. How did those experiences shape your approach to food and foraging?

In Alaska, the fishing jobs are really hard. Long hours, lots of rain, you’re so tired, but it’s so beautiful out there. Watching the salmon run and watching bears and eagles and seals and everybody fish and hunt for the salmon is like being in this other time and place. And then we’d be back in town, and for fun we’d go pick raspberries, because they’re wild everywhere, and make pies. We’d pull crab pots, everyone would come over, we would boil a bunch of crab, and it was fun. The grocery store had really bad food that was clearly really old and very expensive, but your wild food was free, beautiful, and bountiful.

And then I worked on the Yukon Delta in close proximity with Yup’ik natives. . . . I had a couple of women neighbors who would show me how they would break down salmon at their fish-drying camps. They showed me how they used the salmon eggs and salmon sperm, and how they would bury the salmon heads and ferment it. In their relationship with the river, there was no separation between the salmon, the river, and themselves.

“It’s important that we believe we can have a role in Planet Earth doing well.”

When people really care about food, whether it’s a farmer, a fisherman, or a chef, they have a relationship with it. This isn’t just a job or a business. It shapes you. . . . Some people can’t believe I would eat fish out of the [San Francisco] bay, but if the bay is my food source, then I feel very protective of it.

Why is foraging controversial?

It’s interesting. There’s this thought that you’re ruining nature. One seaweed artist said you can’t put seaweed in [your book], because people are going to go out and take all the seaweed. And I say, Well, no, if you teach people how to do it properly, the seaweed will regrow in the same season; it’s then pulled away by storms in the winter. If you’re going to go get mussels, just do it one time a season, don’t take a whole lot, and don’t go to the same place everybody else is going.

In most of the state parks in California, it’s illegal to pick mushrooms, which is insane. They say people go off the paths and trample things, but so do deer, runners, and hikers.

And then there are people who have fruit trees and believe that somebody is casing the fruit tree and comes when everything’s ripe and takes everything. Most of the time, it’s animals doing that.

In my book, I talk about the effects of clear-cutting on the West Coast versus mushroom hunting. They’re not even comparable, but people have a strong emotional response. A big part of the problem is that people inherently believe if humans go into nature, we’re going to mess it up, instead of thinking we could actually have a mutually beneficial relationship with nature, which Indigenous people have been doing for thousands of years.

You write about humans being a keystone species, a species that’s foundational to the life of a system. But you could argue that without humans, many ecosystems would thrive.

There’s a lot of grief, anxiety, and fear right now about climate change. I think there’s this inherent and depressing feeling that no matter what we do, we are hurting the planet.

But there’s also many ecosystems that have thrived with humans for thousands of years; Indigenous people just behave differently. We do have more humans now. But there’s some phenomenal technology advances, like methane digesters that use algae to filter waterways while creating a compost to create feed for cattle. The technology is coming.

I do think it’s important that we believe we can have a role in Planet Earth doing well.

You’ve recently launched an events series called “The Institute for Ecosystem Based Living,” which explores how humans can benefit the planet instead of degrading it. Who is involved in the series?

It’s going to bring together scientists, artists, tech people, and food from the cookbook. At the first event on May 3, Francis Hellman, who is the former chair of physics at U.C. Berkeley, is going to describe dark matter, and Jane Hirshfield will read poems about uncertainty.

“The way I look at ecosystem-based eating is that we learn about nature’s cycle and patterns and try bringing those into our own lives.”

I’ll give you the background for ecosystem-based living as I see it. There is a fisheries biologist named Charles Fowler who was studying the Stellar sea lions in the Bering Sea. [Humans] take millions of pounds of pollack out of the Bering Sea every year; it’s the biggest fishery by volume in the United States. He was looking at its effects on Stellar sea lions and trying to get fisheries management to move away from looking at a single species and instead look at the whole ecosystem.

Instead of saying, “There’s a lot of pollack, so let’s keep fishing them,” [Fowler was] saying, “The sea lions are starving to death, because they’re not getting enough pollock. And the Indigenous people who rely on pollack are not able to hunt them in the winter.” So even if this one species is doing OK, the fishery is having a negative impact on the entire ecosystem.

I looked at ecosystem-based fisheries management and thought about how we can do that as we eat. How can we try to follow natural systems? Keystone species like salmon and oysters make the environment better for all the other creatures, and by doing that, they make it better for themselves.

The way I look at ecosystem-based eating is that we learn about nature’s cycle and patterns and try bringing those into our own lives. When I’m planning my seaweed camps, I’m looking at the low tides; with mushroom foraging, you have to keep an eye on the rain. It’s this way of introducing people to living a little bit more by the laws of nature.

How is knowing how to find or grow your own food “a form of radical independence,” as you write in the book?

I think we have all been convinced that these are the systems, and we have to live with the systems. But if you can step outside of [them] and say, “Well, I’m going to grow my food” or “I’m going to go find my own food,” then you are being highly individual.

The mushroom hunters really know an area, and if you’re out on boats, there’s a lot of self-sufficiency that comes with a sense of being able to survive. There’s much deeper wisdom out there that I feel like I’m just starting to learn.

That’s also really exciting, because every one of these little things opens the door to the next thing. I just started learning about fermenting wild yeast. Right after the latest storms, I was looking for mushrooms and a lot of branches got knocked down, and a lot of them had small pinecones on them. I took some of those pinecones and some of the needles and mixed them with sugar water. I’m now fermenting that into a yeast for a sourdough starter. There’s this whole world of wild yeasts that I find endlessly fascinating.

I think there’s this real desire to have these connections and to have the knowledge. In all of the uncertainty with climate change, there’s probably also a sense that these are good skills to know.

I’ve never thought to cook with pinecones, so I’m curious to know how you learned to cook with them.

Somebody gave me a jar of candied pinecones that they got in a Russian neighborhood in Brooklyn. And then somebody else told me that the Italians eat them. So I looked them up, because they’re often knocked on the ground when I’m out [foraging]. They’re wonderful. They’re very unusual and very intense, but they’re great.

I loved your instructions for do-it-yourself salt and how salt can carry memories of different places. Where do your favorite salts come from?

I love [my salt from] Kachemak Bay in Alaska, and then also one from the Sonoma-Mendocino coast. They’re just so beautiful, and it is that kind of memory or visceral connection you have when you taste it, like being there splashing around. They’ve got a lot going on, a lot of personality. The Kachemak Bay salt is very ocean briny, and the Northern California salt has a tiny bit more seaweed-y umami to it.

I might put some of the salt on my popcorn, or when I’ve made something special—it just adds that relationship element.

This book is focused on the West Coast, but what are the larger lessons for people who live in other parts of the country and are interested in foraging and wild foods?

Whether you’re in a city like Brooklyn or in the Midwest, it’s a matter of giving yourself the time and space to develop a relationship with your surrounding ecosystem. It can get you very excited about spring, and very excited about fall.

Taking a walk is one of the easiest things you can do, and it’s free. You can create this lifelong habit that is good exercise, calms anxiety and stress, and reduces your blood pressure. [You get] really healthy food, and you start developing a knowledge, an almost spiritual element that I think deeply enriches your life.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Herby Mushroom Leek Toasts

Mushrooms sautéed with leek (or onion or shallot) in butter with salt is so simple and adapts to a variety of dishes. These mushrooms can be tossed with pasta, on flatbreads and polenta—or you can add a splash of red wine and make a sauce for pork tenderloin. But my favorite go-to vehicle for wild mushrooms is toasted artisanal sourdough bread. It lets the mushroom flavors shine and works for any culinary mushroom. Make this over a campfire, as appetizers for a party, or if you want it for breakfast, just add an egg. —Maria Finn

Makes 4 servings

3 tablespoons salted butter

1 cup chopped leeks

3 cups chopped wild mushrooms (see note)

1 teaspoon kosher salt

½ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

½ teaspoon finely chopped fresh herbs (like rosemary, thyme, or sage)

4 slices ¼-inch-thick sourdough bread, toasted

⅓ cup shaved Parmesan

Note: You can use any culinary mushroom for this. Just keep in mind if you’re using chanterelles or any other mushrooms that absorb a lot of water, you’ll want to dry-cook them first to get the water out. And if using black trumpets or yellowfoot chanterelles, no need to chop them if they’re small.

Directions

In a large pan over medium-high heat, melt the butter and add the leeks. Sauté until translucent.

Add the mushrooms, salt, pepper, and herbs and cook until everything is browned, 6 to 7 minutes. Plate the toasts, pile mushrooms on top, and garnish with the Parmesan.

This recipe is excerpted from Forage. Gather. Feast. 100+ Recipes from West Coast Forests, Shores, and Urban Spaces by Maria Finn. Reprinted with permission from Sasquatch Books. Publication date: April 9.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

WOW!