A version of this article originally appeared in The Deep Dish, our members-only newsletter. Become a member today and get the next issue directly in your inbox.

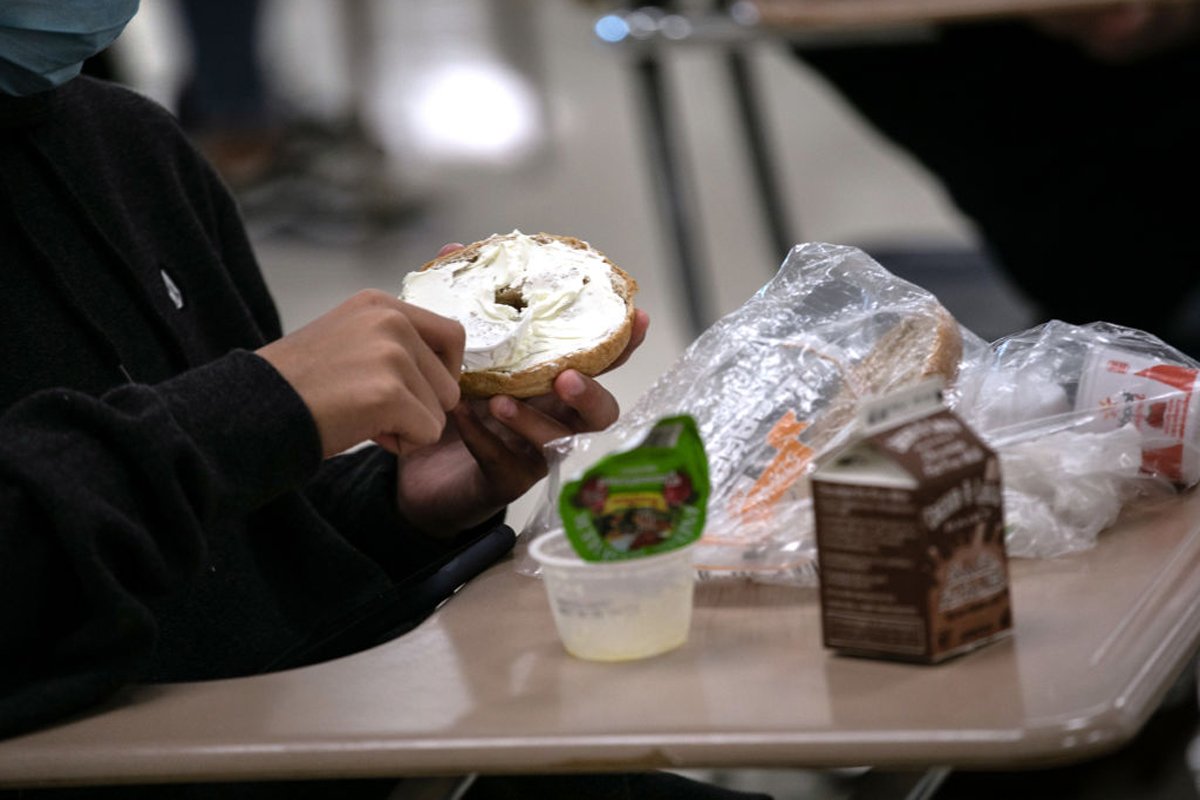

The pandemic revealed both the strengths and weaknesses of the country’s school meal programs. In some cases, this unique time led to opportunities for local farmers to provide food directly to school districts. It also ushered in a wave of emergency allotments, which offset family food costs and significantly decreased food insecurity. However, when those funds came to an end, it exposed how many families struggled as the costs of groceries ballooned and universal free meals disappeared in most states.

“We’ve made them seem like charity handout programs, but they’re multi-sectoral, complex programs that actually contribute significantly to economic development, short and long term.”

In 2021, the Global Child Nutrition Foundation (GCNF), a nonprofit that provides global monitoring and advocacy to support the development of school feeding programs, ran a survey to capture the state of school meal programs across 139 countries—representing 81 percent of the world’s population.

This is the second GCNF global survey (the first was in 2019) and it collected data for the school year that began in 2020, highlighting 183 programs with large-scale meal programs. The goal is to track the programs’ progress and standardize their evaluation of coverage, beneficiaries, funding, links to local agriculture, and more.

Arlene Mitchell, GCNF’s executive director, believes school meal programs are misunderstood. “We’ve made them seem like charity handout programs, but they’re multi-sectoral, complex programs that actually contribute significantly to economic development, short and long term,” she said.

We spoke with Mitchell about what the survey revealed, how the United States’ program stacks up to other school meal programs around the world, and how it can improve.

What does a good school meal program look like?

There are a number of factors that we consider. One is, are they covering the need? [And then] how comprehensive it is—is it more than just feeding kids? [Does] it include some nutrition education, some knowledge of where food comes from? In some cases, it includes things like children helping to prepare or serve the food. They’re actually engaged in the program more meaningfully.

A third factor that we look for is a set of things that can contribute to sustainability, or to keep the program going. Are they engaging meaningfully with local farmers so that there is some economic opportunity locally alongside the program? Do they have a healthy relationship with the private sector in their country? Is it creating jobs? Is it in the national budget in a way that means that it can be sustained?

You look at countries at all levels of income and development. Which of the low-income countries stood out to you? Which ones did an exceptional job working with the resources that they have?

There are some pretty stunning examples of low-income countries actually trying harder, proportionately, than some rich countries to address hunger and nutrition in their school-aged kids. For years, one that has been astounding to me is Burkina Faso, one of the poorest countries in the world. Something like 89 percent of the budget for school meals is coming from the government, a very high percentage for a low-income country. And they’re covering almost 100 percent of their [elementary] school students, which is just extraordinary.

After the Millennium Development project in the early 2000s took off, several African countries pledged to implement new programs. Ghana has a very impressive program. Kenya has a pretty impressive program. Nigeria is new to the scene; their program now is very impressive and expanding quickly.

“There’s a lot to be proud of in the program. But one of the biggest issues is that the country has lost its excitement about it.”

Let’s jump to the U.S. What are some of the strengths of the programs here?

Like the story?

Join the conversation.