The cost of specialized farm equipment is one of the biggest barriers for small-scale and beginning farmers. Cooperatives are springing up around the nation to help bridge the gap.

The cost of specialized farm equipment is one of the biggest barriers for small-scale and beginning farmers. Cooperatives are springing up around the nation to help bridge the gap.

January 8, 2024

Elias, son of Nathanael Gonzales-Siemens, uses the collectively purchased combine to harvest safflower. (Photo courtesy of Nathanael Gonzales-Siemens)

For three years, Nathanael Gonzales-Siemens drove up California’s coast for 14 hours every month for a routine task: milling his grain into flour. “I was literally not able to find a flour mill at my scale, and we’re not tiny,” he said. “We’ve got 150 acres of grain.” He found this disconcerting, not only for himself but the future of small-scale grain farming in California, once known for its golden hills of grain.

As California has lost much of its grain to higher value crops, small flour mills and grain cleaning businesses have disappeared, too. It’s a symptom of what Gonzales-Siemens sees as a larger problem facing many farmers, awash in a marketplace dominated by highly concentrated operations as regional farm infrastructure atrophies. This specialized, often professionally operated equipment—and all farm equipment, for that matter—can be prohibitively challenging for many farmers to buy and maintain.

“This does not feel like I am living on planet Earth, where humans live,” said Gonzales-Siemens, laughing at the absurdity of the drive north to find a mill.

“It’s not a novel idea. Farmers have been sharing equipment forever. But it seems like farmers are becoming less and less neighbors of each other.”

He eventually bought a mill from a grain farmer who went out of business, but finding the other equipment necessary for both farming and processing grain was an ongoing struggle.

So, Gonzales-Siemens got to talking with other farmers in the region. He learned nearby grain farmers, Clayton Garland and Melissa Sorongon in Santa Barbara, were in a similar position. In 2019, the trio decided to work together to lift this equipment burden, pooling funds to buy their first combine. Prior to that, they had all either harvested by hand, an intensely laborious process, or hired someone with a combine. Next, they purchased a no-drill seeder together, and it allowed them to plant rows of grain directly into orchards and pastures without tilling, a practice known to benefit the soil.

As word spread, other small-scale farmers joined them, and they became a more formalized collective with a name: California Plowshares.

“It’s a programmatic way for us to be a little more collaborative and supportive of each other’s work,” said Gonzales-Siemens. “It’s not a novel idea. Farmers have been sharing equipment forever. But it seems like farmers are becoming less and less neighbors of each other. Most of my neighbors—the people actually adjacent to me—are corporate entities,” where the farm owner is often absent, and the workers don’t have a say in the equipment.

In this sense, California Plowshares is a return to the kind of rural sharing economies that once arose naturally between farmers in tight-knit communities but have become much less common in recent years. The collective currently consists of around 50 farmers located along California’s southern Central Coast who share equipment that they co-purchase and individually own, often with a rental fee.

The original idea was to form a collective for just grain farmers, given that “grain farming is so rare that we need all the infrastructural and equipment help we can,” said Gonzales-Siemens. But then it became clear that the collective could benefit a wide range of small-scale farmers.

The collective doesn’t charge a membership fee, but they each contribute in other ways. There’s the “sweat equity type of guy,” who jumps in wherever needed. Another farmer with storage for equipment. Others chip in financially when they’re having a good season. There’s a skilled welder who fixes loose parts. As for Gonzales-Siemens, he often helps transport equipment between farms. They tend to lean on each other’s strengths.

In the near future, he hopes to contribute further by building out a local grain processing operation, filling a gap in regional infrastructure. He is now the proud owner of three flour mills, two of which he shares, and the co-owner of a grain cleaner—the building blocks of the processing operation in the works. Long gone are his days of driving up the coast to find a flour mill, and he hopes to spare other farmers from that fate as well.

Collective approaches to farming, like equipment sharing, often emerge from a stark realization: The current farm business model in the U.S. isn’t working for many small producers. The median farming income in the U.S. was less than zero in 2022: -$849. Meanwhile, the cost of farm production expenses are expected to reach a record high in 2023. It’s a balance sheet that isn’t adding up, and equipment is a part of the equation.

“We thought it was so stupid to have all this steel sitting in the field that we were using just twice a year.”

Next to land, equipment is a farmer’s biggest investment. While farm equipment collectives are still relatively rare in the U.S., they tend to share a similar origin story: Farmers begin informally swapping farm equipment to ease costs, building a sense of trust. Then they realize that sharing tools makes sense and they build a more formal system. This is the story of Tool Legit (yes, named after the MC Hammer song), a farm equipment library in North Carolina.

“It started off with a couple of buddies. I owned the tiller. Someone owned a bush hog. Someone owned a flail mower. We would just swap them back and forth as needed,” said George O’Neal, a vegetable farmer who started Tool Legit. “We thought it was so stupid to have all this steel sitting in the field that we were using just twice a year.”

In 2011, they formed an LLC with a rotating president and treasurer, supported by a $27,500 grant from the Rural Advancement Foundation International (RAFI). This helped them buy their first cache of shared equipment: a tiller, a harrow, a manure spreader, a trailer to move equipment between farms, and a log splitter for heating greenhouses with wood. Every year, they pool funds to add to their growing collection of tools.

A decade later, the collective is still thriving. “We’re all very community and civically minded, but I feel like that’s very true for 90 percent of small farmers,” said O’Neal. “We don’t see each other as competition in any meaningful way. We see Walmart or shitty food or HelloFresh as competition—not each other.”

O’Neal estimates that he saves about $1,000 every year in equipment upgrade costs. The collective charges an annual membership fee, but aims to keep it low, below $400 per year, so it’s accessible.

It helps that, like California Plowshares, Tool Legit has low overhead costs; they store the equipment on their farms and use Google Calendar to reserve it. Other equipment-sharing models involve renting space, a system that works for some farming communities but can add to the costs.

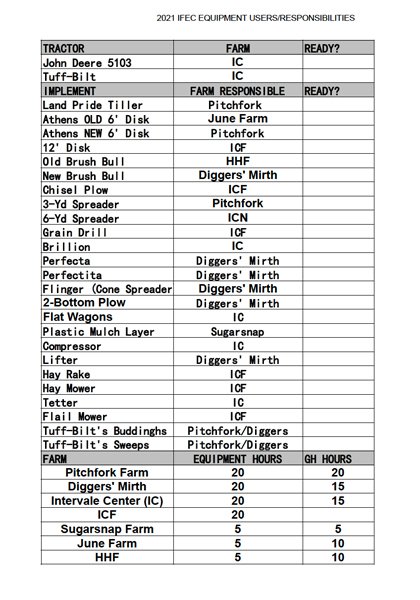

The list of equipment shared between the farmer members of the Intervale Farmer Equipment Company in Burlington, Vermont.

One example is the Intervale Farmer Equipment Company, a farmer-owned cooperative in Burlington, Vermont. Hilary Martin, one of the farmers in the cooperative, said the space they rent is their largest expense annually. They spread out the cost through a fee structure based on either the number of acres on which the equipment is used or the number of hours it is in use. It’s an evolving system, said Martin.

“Every year we have to take a look at [whether] we’re charging enough,” she added. “We’ve been well in the black some years, and other years we’re in the red.”

So far, they’ve been able to accommodate seven farms of varying size. They have the advantage of being close neighbors, and all rent land from the Intervale Center, a nonprofit that supports farm viability. The center originally owned the equipment cooperative, then sold the business to the farmers. “We’re kind of pre-organized to work together,” said Martin.

Still, she wasn’t sure they’d be able to make it work. “I was worried about a tragedy of the commons scenario . . . people would be in a rush, misuse the equipment, and leave problems for everybody else.” Instead, she has been pleasantly surprised by her neighbor’s capacity to look out for each other.

The range of equipment available in collectives also allows for experimentation, giving the farmers the freedom to test out what works. It also allows them to try out more regenerative practices, which typically require new equipment.

For instance, prior to the formation of California Plowshares, none of the group’s members owned a spreader for mulching, which helps retain moisture in the soil. Once ubiquitous, spreaders have become harder to come by in California’s Central Valley, where many of the corporate farms hire private companies to deliver and spread mulch. The companies are often booked months in advance. “To get [your mulch or compost] spread in a timely manner was really quite impossible,” said Gonzales-Siemens.

“Building efficiencies and healthy movement patterns into your farming business is such an important way to protect yourself and not burn out.”

Everything changed when the collective bought a small-scale spreader from the 1980s, relying on a grant they obtained. Now, the farmers’ soil will be better protected during dry times of the year. Similarly, buying a no-till drill allowed Gonzales-Siemens to expand the use of cover crops in his orchards and further protect the soil.

“[The drill] made a huge difference. It has allowed us to do much more creative things in orchard systems,” said Gonzales-Siemens. It’s also helped him experiment with intercropping, another practice that builds soil health and biodiversity on the farm. And, at $6,000, he wouldn’t have been able to afford one on his own.

Over at Tool Legit, the farmers share similar goals of farming ecologically and productively at a human scale, which lends to knowledge-sharing, too. “It functions kind of like an informal discussion network,” said O’Neal. “Every time you go pick something up, there’s usually a 15- or 20-minute chat, like, ‘What are y’all up to today? Oh, that’s cool. I’ve never seen that. What is that? What are you growing?’”

Nathanael Gonzales-Siemens demonstrates how to use California Plowshare’s no-till drill to grow cover crops in an orchard. (Photo courtesy of Nathanael Gonzales-Siemens)

They’ll also often advise one another on the best, most efficient ways to use the equipment. For instance, O’Neal said farmers will send the entire group a text, such as, “Hey, I offset the potato digger and it can do two rows at once. Has anyone tried this?”

Connecticut farmer Mary Claire Whelan, who helps run a new tool-sharing network with the New CT Farmer Alliance, has also observed the mental health benefits that come from having a supportive network of farmers and access to the right tools and equipment.

“It’s so emotionally draining to use the wrong tool over and over again,” said Whelan, who works as a farm crew member on a vegetable and flower farm. “Building efficiencies and healthy movement patterns into your farming business is such an important way to protect yourself and not burn out.”

She recalls working on a previous farm where she was required to break heads of garlic into individual cloves for planting. “It’s hard on your thumbs. I would get all these calluses,” she said. Then she learned of a tool that can quickly split garlic heads. It could have finished the task in a few hours, saving days of hard, repetitive labor.

Whelan hopes to one day own her own farm in Connecticut, the state that she notes has some of the most expensive farmland in the country. She sees building social and resource networks as essential to making it as a first-generation farmer.

Connecticut farmers standing in front of a winnower, built by Dina Brewster, which she has made available for nearby farmers to share. (Photo courtesy of Dina Brewster, Hickories Farm.)

“I don’t think [owning a farm business] would be possible if I didn’t have a robust community to rely on and folks who I could borrow equipment from, or purchase it in common with,” she said. “It helps me feel like the future I desire and see for myself is a possibility.”

Despite these benefits, farm equipment collectives and sharing models are still few and far between in the U.S., especially compared to other countries. France has the most developed sharing system, which includes a network of over 12,000 agricultural equipment cooperatives, involving a third of all French farms.

These cooperatives have allowed farmers to share equipment and infrastructure, including compost facilities, and have been integral in helping a growing number of farmers there adopt agroecological practices. “Since the 1980s, some Coopérative d’Utilisation de Matériel Agricole (CUMAs) have taken initiatives that pertain to agroecology: purchases of specialized harvesting equipment necessary for more diversified farming systems,” observed French scholars Veronique Lucas and Pierre Gasselin in a 2022 article.

There have been some recent efforts to support more robust farm equipment-sharing in the U.S. Earlier this year, California Assemblymember Steve Bennett introduced a bill aimed at funding regional equipment-sharing hubs for equipment needed for soil health and conservation practices, as well as storage and processing. It also would have provided training for farmers on how to design their own equipment cooperatives. The bill passed in both the Senate and House last spring, but it was vetoed by the governor due to budget concerns.

“It just makes sense to have it be a piece of equipment that gets rotated around and shared,” Assemblymember Bennett told Civil Eats. And while he’s not ready to commit to introducing the bill again next year, he’s considering it.

Faith Gilbert, the author of a popular guide on tool-sharing, attributes the slow uptake in the U.S. to the effort it takes to organize. “Few of us have time to go organize a whole new program in order to save $3,000 to $5,000 annually,” she said. And while sharing farm equipment can chip away at the high costs of farming, she notes that “it’s not going to fundamentally shift the business model” of most farms.

Still, she acknowledges, most small-scale farms work with small margins, and any boost to the bottom line can make a difference.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 24, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.