In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

June 17, 2021

One of my earliest memories is of sitting with my father beside a warm incubator and watching soft, fuzzy baby chicks emerge from their eggshells, one tiny chirping beak at a time. I was too young to go to school, but he was already teaching me about taking responsibility for raising livestock and holding a significant role in the food security of my family and community.

When I was born, my father—who was born in 1934—was already considered an elder among the Oceti Sakowin (Dakota/Lakota Sioux). I was blessed to receive much training from him about Indigenous foodways from an early age. At the time, I didn’t realize how extraordinary that was, but as I grew older, I saw that most people my age or younger had not received the same lessons.

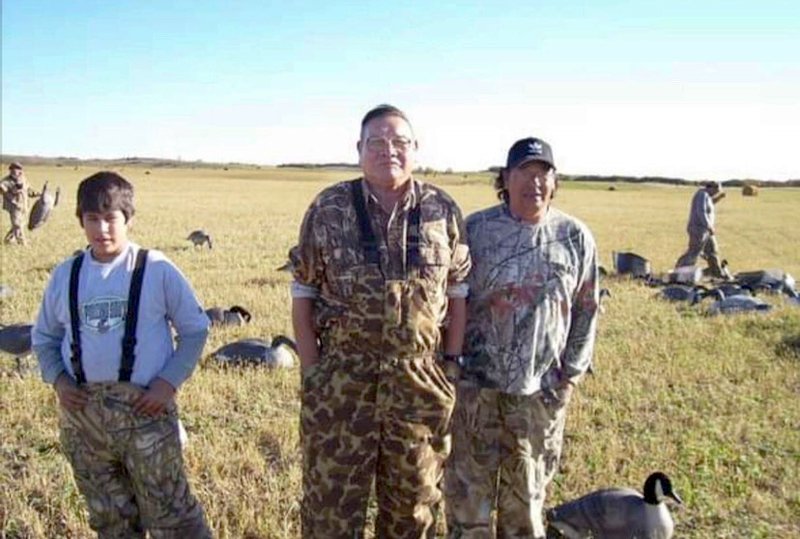

It was important to him that I know how to grow things and properly tend to them. We kept pheasants, ducks, and chickens, and a vegetable garden every year. Harvest time was always busy for us. Wohanpi (soup) made with dried corn and dried meat was considered a feast by older relations.

I also learned how to hunt and fish, as well as skin, butcher, dry, and prepare wild game using customary Oceti Sakowin techniques. I was also taught how to recognize and identify various fruits, vegetables, fungi, and plant medicines growing in the wild. Some of my father’s favorites were pemmican and wojapi, as well as all manner of jams and jellies. We did a lot of canning in the fall. And we didn’t need to venture off the Reservation to visit the grocery store very often. What he taught me, without saying it, is the importance of food sovereignty—our right to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and our right to define our own food and agriculture system.

I was fortunate to have all this passed down to me before my father died from COVID-19 in November. But not everyone who was lost had a chance to pass along their food traditions to this extent, meaning that in addition to being a plague of historic proportions for Native Nations, the COVID-19 pandemic will also undoubtedly result in lost information about how to gather, raise, and prepare food.

Data is missing, and we may never know how severely Tribes were effected, but the Centers for Disease Control has concluded that the cumulative incidence of lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases among Native American people was 3.5 times greater than that of White people.

As Natives, we saw the disproportionate impact with our own eyes, as we endured months of lockdowns, quarantines, economic hardship, and witnessed friends, relatives, and beloved community members get sick, suffer in agony, and die from the virus.

Our ceremonial practices are crucial to our cultural identities and lifeways, but the coronavirus robbed us of that as well. We couldn’t hold healing ceremonies or customary funeral services because they put others at risk of contracting the illness.

Like other groups, our oldest members were most vulnerable to COVID-19—but the difference between us and mainstream society is that Native communities hold elders in high regard and cherish them. Since pre-colonial times, Natives have observed oral tradition. We understand that elders, who learned from previous generations and have accumulated a lifetime of their own experiences, are one of our most valuable resources. They are repositories of priceless ancestral knowledge, and so much of it has never been written down.

After Columbus landed, people Indigenous to the Americas were subjected to hundreds of years of genocide, through disease, starvation, forced removal, and outright murder. Since the Reservation era began in the late 1800s, tribes throughout the United States were subjected to assimilation. Children were taken away from their families and homelands and taken to boarding schools to be taught how to live as a White person, or “kill the Indian, and save the man.” They quite literally had their Native languages beaten out of them. For this reason, most Native languages are on the verge of extinction. Today, most of our fluent speakers are elders, and we’ve lost many of them as a result of this pandemic.

We also lost many keepers of traditional foodways.

We are children of Ina Maka (Mother Earth), and we have our own traditional methods of hunting, gathering, planting, preparing, and storing food that are specific to the environment we in. We learn these ways from our elders.

For this reason, losing so many of them suddenly from the virus puts that information in danger of disappearing forever. Due to imposed poverty on most reservations and their isolated nature that cause them to be food deserts, Native communities currently struggle with ensuring that their populations have adequate, healthy nutrition. As it is, American Indians and Alaska Natives have a greater likelihood of getting Type II diabetes than any other racial group in the United States. We need every bit of ancestral knowledge saved. Our lives are at stake without it.

Tribal preservation offices throughout the country are working to document all the knowledge and collective wisdom that elders wish to share, primarily by recording their words, and tribal colleges located on reservations often provide elders with a venue to give lessons that teach traditional foodways, as well as skills like tanning hides and working with medicinal herbs. This is one way we are fighting to save ancestral teachings. Contrary to what some may believe, technology can be a useful tool in the process of decolonization and helping to preserve and revitalize Indigenous ways.

Our ancient food practices are dependent on the well-being of the ancestral lands we live upon. All of our teachings, nutrient sources, and cuisine are based on the landscapes we’ve lived in for thousands of years. A core part of our belief system is to think of the next seven generations in all that we do, too. It is our responsibility to ensure that the land that is their birthright is protected and will still be here when they arrive. This is why we are so dedicated to protecting our land and water, to the point of putting our bodies in front of bulldozers that threaten them.

While traumatic and harrowing, the pandemic gave me a greater appreciation for what my father taught me. Last spring, I planted and preserved my own tomatoes, potatoes, squash, onions, and pumpkins, and cooked wonderful meals with my own organic, homegrown ingredients throughout the fall and winter. My daughter harvested her first whitetail deer, and we made venison stew with the meat. As traditional Oceti Sakowin, we offer tobacco and a prayer of thanks for the bounty.

I’m happy that my father got to see me make full use of everything he handed down to us before he passed. We were devastated when he was taken from us. Native communities everywhere are in a state of grief from all we’ve lost. No family is untouched by the virus. Yet, we are strong in our sadness and carry their memories with us. They are a part of us, and we remain because of their sacrifices. Their knowledge will not die. This storm, like all those that have gone before, will pass—and we will thrive.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.