Over half of the population of Stockton, California, is diabetic or pre-diabetic. A prescribed meal kit program helps some residents manage the disease and may provide a model for other communities.

Over half of the population of Stockton, California, is diabetic or pre-diabetic. A prescribed meal kit program helps some residents manage the disease and may provide a model for other communities.

January 22, 2024

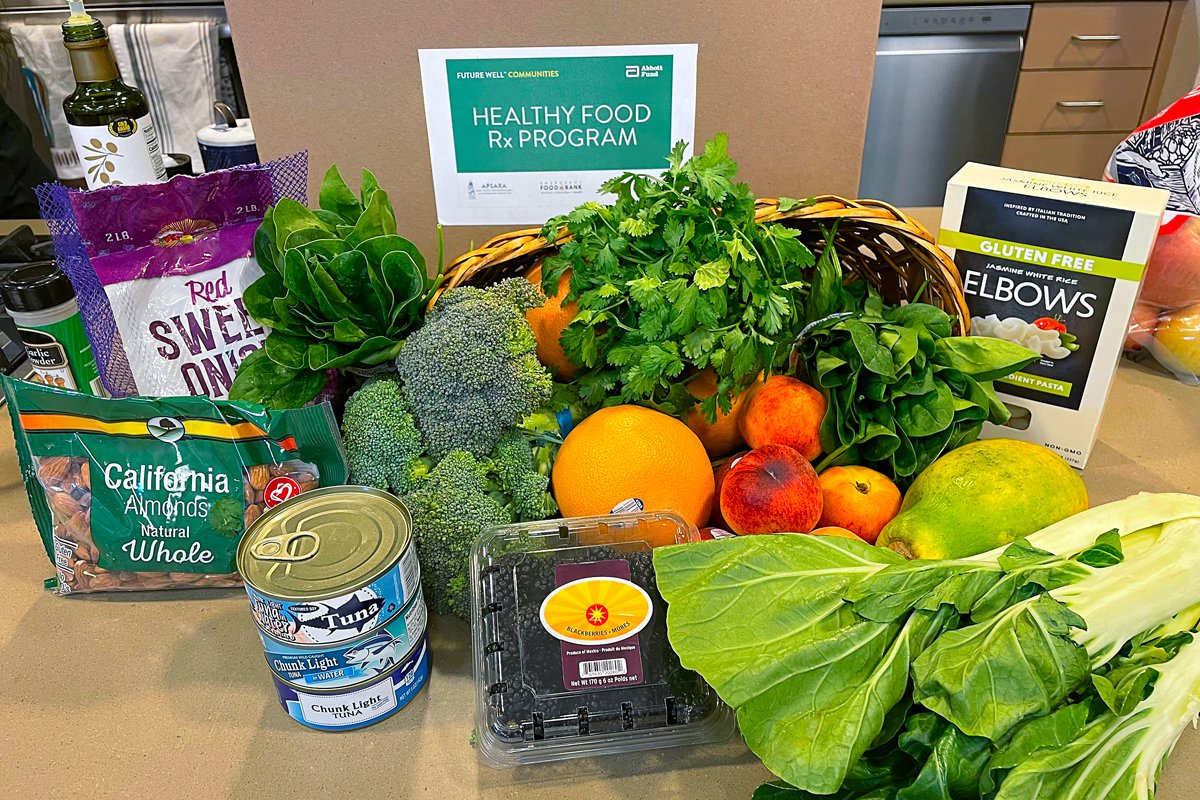

A participant in the Healthy Food Rx program gets ready to prepare a recipe with the fresh produce she received in one of its meal kits. (Photo credit: Abbott Fund)

Recently, at age 72, Shane Bailey changed her grocery store routine. Her first stop is now the produce section to pick up kale, her new favorite food. She prepares it with collard greens, mixes it into stir-fries, and boils it in vegetable broth. Another new love is white sweet potatoes mashed with a dab of butter. She also has a new go-to sandwich: avocado, low-fat mayonnaise, white onions, and alfalfa sprouts between toasted rye bread. “Oh my God, it’s to die for,” she said. She then raves about donut peaches. “Google it!” she insisted. “It looks like a donut, but it’s a peach.”

Bailey was introduced to these new kitchen staples through a prescription meal kit delivery program, known as Healthy Food Rx. A collaboration between local community organizations, the Public Health Institute (PHI), and a large philanthropic fund, the 12-month program delivered meal kits twice monthly for adults with diabetes in Stockton, California. Although the city is located at the top San Joaquin Valley, a major agricultural region, fresh produce is sparse and people in many Stockton neighborhoods struggle with food insecurity.

“It has taught me how to cook things, like dandelion greens and kale, that I never knew existed. It has been very educational.”

Over half of the town’s 320,000 residents are diabetic or prediabetic, according to PHI. The Healthy Food Rx program aims to help change that, recognizing the large body of research linking food insecurity and diabetes. So far, the approach—delivering meal kits with enough food for two meals and pantry staples, paired with nutrition fact sheets and cooking lessons—appears promising in managing diabetes.

Along with addressing the sharp rates of diabetes in Stockton, a larger goal of the program is to build the case for a program like this to be treated as medicine. It’s part of a nationwide food as medicine movement to prescribe nutritious foods, recognizing the medical capacity of food to help manage or prevent chronic diseases.

So far, the majority of programs under this banner prescribe fruits and vegetables or medically tailored meals that have been pre-prepared and designed to support a particular condition. While home-delivered meal kits have yet to gain widespread traction as a medical intervention, advocates hope that it could offer a more educational approach—while eliminating transportation issues—to supporting people with chronic diseases, which is nearly half of the U.S. population.

After just six months, Bailey attributes to Healthy Food Rx a dramatic shift in her diet despite a lifetime of ingrained habits. She especially loved the optional cooking and nutrition classes that were offered alongside the meal kits. “It has opened up a whole new area in my shopping list under fresh vegetables,” Bailey said. “It has taught me how to cook things, like dandelion greens and kale, that I never knew existed. It has been very educational.”

The shift has also helped her better manage her Type 2 diabetes. She’s observed a reduction in her A1C levels, a measurement of blood sugar levels used to diagnose diabetes, which fell from 7.2 to 6. It’s a significant drop: An A1C over 7 is considered uncontrolled diabetes, increasing the risk of other health complications. Now, her blood sugar levels are in a manageable range. She’s also lowered her dosage of the diabetes medicine Trulicity.

“In general, as we get more and more research, we’re learning that diet plays a role in everything.”

Of course, Bailey’s outcomes may be also attributed to her mindset, one particularly receptive to change. She calls herself a “lifelong learner,” and because she’s retired on a fixed income, she seeks out every free educational opportunity she can find.

This is a broader problem with evaluating lifestyle change programs: They tend to draw people motivated to change. That said, other participants in the program also saw their A1C levels fall into a healthier range.

In fact, an internal study of 450 program participants found a clinically significant decrease in A1C levels—an average 0.8 percent decline—within 12 months for participants with uncontrolled diabetes. The study participants also reported that the dietary shifts helped them exercise and take health education classes more often.

While the study’s limitations make it comparable to an internal evaluation—there’s no control group or peer review—it points to initial promise of meal kits that utilize fresh fruits and vegetables in managing diabetes. (Bailey, who is still in the program, wasn’t in this study.)

Most of the participants stuck with the program, too: Eighty-five percent stayed for the first six months, and 64 percent stayed for all 12 months. That’s a higher retention rate than other prescription produce programs typically see. Maggie Wilkin, the study’s lead author and the director of research and evaluation at PHI, said the way the kits help participants prepare meals provides a low barrier for participation—the education classes are optional and the kits are delivered by DoorDash, which partners with over 300 anti-hunger organizations.

And it certainly helps that the food is enjoyable. “The feedback we get on these recipes is phenomenal,” said Alex Marapao, a nutrition educator at Stockton’s food bank who is responsible for packaging the meal kits. She curated them with the town’s predominantly Latino population in mind, developing recipes that were nutrient-dense and culturally appropriate, while exposing people to new, easy-to-prep dishes like pressed kale salads. They’ll also throw in staple foods such as eggs, brown rice, or Greek yogurt, depending on what’s available.

Francesca Castro, a clinical research dietitian at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center who was not involved in the study, was encouraged by the results. “The diabetes results are definitely promising, especially the retention rate,” she told Civil Eats. However, she still considers it preliminary. “These studies are helpful to build the bigger argument and to help build the case for more rigorous studies down the line,” she said.

“In general, as we get more and more research, we’re learning that diet plays a role in everything,” added Castro.

Currently, doctors refer patients to the Healthy Food Rx program, but the hope is for it to be one day prescribed by doctors and funded by Medicaid and private insurance.

Food as medicine programs are now in the early stages of being formalized into health care settings and insurance coverage. So far, a handful of states—including Massachusetts, Oregon, California, Arkansas, New Jersey, and North Carolina—have received temporary approval by the federal government to cover food as medicine programs under Medicaid. The approval was granted in most states through a five-year, experimental waiver.

“Unfortunately, we saw during Covid that diet-sensitive diseases were a huge predictor of more severe disease.”

“We have fortunately a lot of programs being integrated into Medicaid right now under our federal waiver. The goal is that these will be permanent benefits under Medicaid here in California,” said Katie Ettman, the food and agriculture policy manager at the think tank SPUR and a member of the Food as Medicine Collaborative. “The idea is that we’re setting up long-term sustainable funding and access for patients.”

Last year, SPUR and the Food as Medicine Collaborative worked with lawmakers to introduce a bill that would make California’s food as medicine programs a permanent provision of the state’s health insurance plans under Medicaid, but it didn’t make it through the state legislature. Ettman said they plan to introduce it again later this year.

Prior to the use of this waiver, food as medicine programs were largely philanthropic efforts by nonprofits or hospitals with community benefit spending. “They were . . . helping to improve health outcomes, but they weren’t necessarily being treated like any other health care provision,” Ettman said. The programs often benefit from philanthropic efforts, but that funding can be sporadic and short term, leaving patients hanging.

“I remember the moment when we [had to tell patients], ‘This is the last prescription that we can give out,”’ said Emma Steinberg, a pediatric hospitalist dividing her time between San Francisco and Boston. “It’s a pretty terrible feeling as a provider to have had this really amazing tool that works well . . . and then have to be like, “Oh, sorry, no, we can’t do that anymore, because there’s just no money for it.”

Yet Steinberg is hopeful that this will begin to shift as the evidence continues to build for the role of nutrition programs in managing chronic disease. It’s a connection that she said became more glaring during the early pandemic. “Unfortunately, we saw during Covid that diet-sensitive diseases were a huge predictor of more severe disease,” she said.

Since the early pandemic, people in Stockton have faced deepening food insecurity. The town’s emergency food bank has observed a steady uptick in clients. In 2022, the food bank reports that it served nearly 300,000 families from the town and surrounding country, which has a population below 800,000 people. This surpasses the number of families it served in 2019 by 141 percent. Both a rise in food prices and end to pandemic-era food aid have made the lack of access to food there much more dire.

This makes food interventions, like the Healthy Food Rx program, all the more critical. But like many food as medicine pilots, it’s not clear how long it will continue. “We are looking into ways to make this program more sustainable over the long term,” said Maggie Wilkin, the study’s lead author. While the initial study has ended, she said they will soon start recruiting for another study on the Healthy Food Rx program, while expanding the food box deliveries to 800 to 1,000 participants from Stockton.

A meal kit distributed through the Healthy Food Rx program includes fruit, vegetables, and pantry staples such as nuts and canned tuna. (Photo credit: Abbott Fund)

Wilkin also points to how the program’s local partnerships—with the food bank and the referring federal health clinic—have helped participants continue to receive nutrition and diabetes support even after their 12-month cohort wrapped up. Some are still visiting the food bank.

“It’s really important that you have that infrastructure to provide some sort of sustained health outcomes rather than just a one-time produce prescription,” said Wilkin, who adds that the program is part of a wider support network for diabetes patients.

Participant Shane Bailey is continuing to receive food boxes for another few months as part of an ongoing study. “I think it should continue forever,” she said. “I would love to have the box every week, not every other week.” Regardless, she won’t stop making a beeline for the produce section for her new favorite foods every time she enters the grocery store.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 24, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.