In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

April 9, 2021

Deep inside the food industry’s research laboratories, scientists not only exploit food additives, but they also harness the latest brain science and cutting-edge technology to keep us wanting “just one more.”

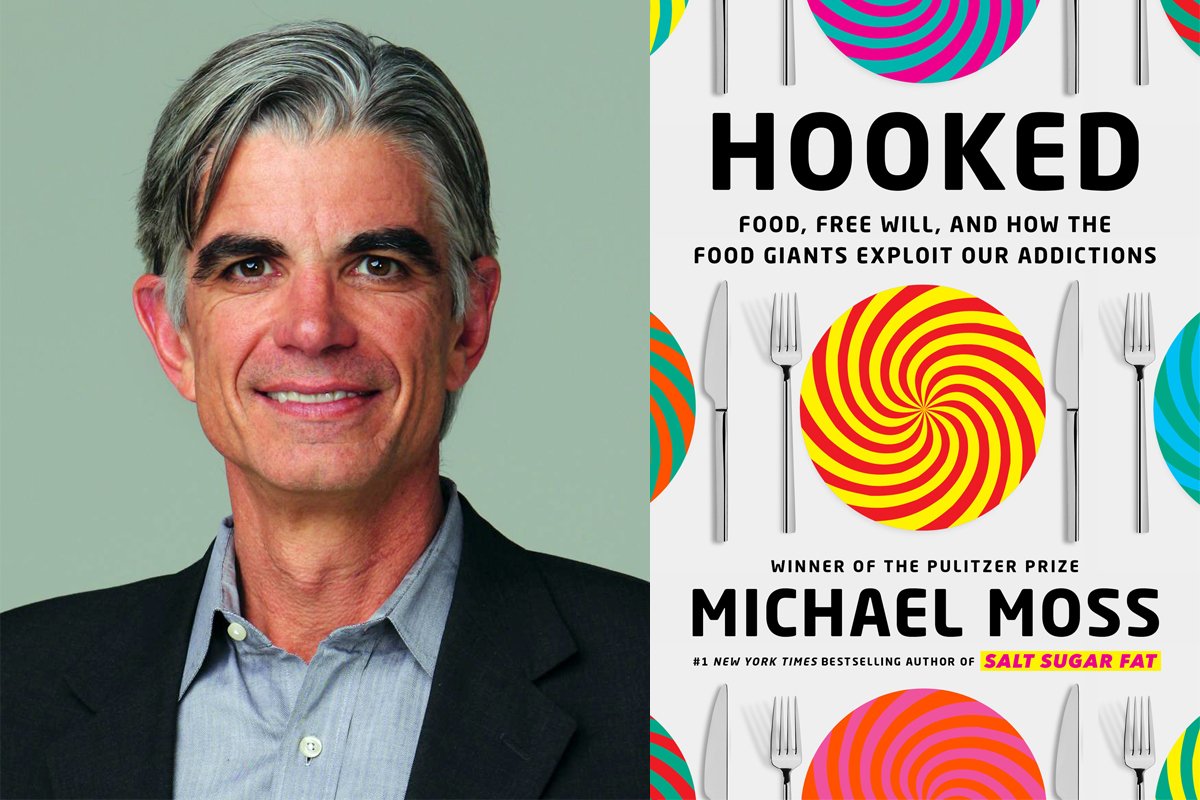

Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative reporter Michael Moss first explored this dark side of processed food production in his 2013 book Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us. While promoting the book, Moss was often asked whether processed foods are merely hard to resist or actually addictive—on a par with substances like tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs. But by his own account, he “hemmed and hawed, not knowing the answer, though aware that the implications could be huge.”

In his latest book, Hooked: Food, Free Will, and How the Food Giants Exploit Our Addictions, Moss addresses the question of food addiction head-on, determined to finally “sort out and size up the true peril of food.”

Civil Eats recently spoke with Moss about our biological vulnerabilities to processed food, how the industry both creates and exploits our childhood food memories, and why making spaghetti sauce from scratch is a political act.

Let’s start with the pandemic. In Hooked, you explore how stress, fatigue, and painful emotions can all fuel our food cravings, so I’m guessing you aren’t surprised that snack food and candy are selling especially well right now?

Actually, I was surprised to see snack sales soar during the pandemic. I was thinking at least we were getting away from the vending machine at work, yet here we are, turning our kitchen cabinets into vending machines. We went to the store and we just got walloped by these powerful memories, taking us back to our childhood and that craving for comfort food under stress. In fact, I wrote a piece in the [New York] Times a few months ago about how companies shifted their marketing to capitalize on the pandemic, which is totally sinister and cunning on their part.

I think the lesson from drug addiction—and one reason I wrote Hooked—is that our decision-making about what to buy and how much to eat can be so spontaneous and impulsive, especially in light of companies’ marketing. Like recovering addicts, we have to do more than just [understand] what they’re doing to us. We have to plan ahead. When you go shopping, you need to have a list and stick to it because they’re doing everything they can to get you off that list. Impulse buys are where they make a ton of money.

Do you think we should regulate food marketing the way we regulate the marketing of tobacco?

Being a journalist, I’m kind of agnostic [about regulation]. But what does seem to help many people cut back on their smoking are two things: warning labels on cigarettes and taxation, because we love money as much as cheap food. So, that kind of “nudge marketing” could be really effective, and obviously they’re trying that with sugar taxes in certain cities. I came full circle on those—I love those now, especially if the money collected is put back into relevant programs that help people shift toward better eating. But I put industry and government into the same pot: There are some things they can do, but time is short. So, I keep putting the onus on us to change how we value food, to find ways to do that ourselves.

Yet as Hooked explores in detail, the industry marshals tremendous resources—huge amounts of money, the brightest scientific minds—against our vulnerable biology. Is it realistic to expect us to overcome those forces?

No. [Laughs.] You’re totally right. I’ve had this dream of being able to take one ZIP code in the country and change 10 things that need to be changed about our food environment in order to help people change their eating habits. And you would start by planting a garden in the elementary school—not just to feed the kids, but to get them excited about radishes so they bring those radishes home and get their parents excited. And then you have to figure out how to make radishes more affordable than a three-cheese frozen pizza. And then you realize the whole farming system is skewed toward processed food.

Some of that involves government intervention, but there are a lot of nongovernmental entities that are working on those things too. So, my hope lies in those NGOs that are fighting to get gardens into schools and to reinstate home economics—but home economics from a political framework, not just preaching to kids about food.

But without governmental intervention, do you think food companies will ever mend their ways on their own?

I think we feel a little disappointed [by the Obama administration.] I mean, hats off to Michelle Obama for making food such a big part of our conversation. But when it came to coercing the big food companies to truly change their ways, that didn’t happen. So, that’s why I’m pessimistic on that front. I still like to think of food companies not as this evil empire that intentionally set out to make us sick, but as companies doing what all companies want to do: make money by selling as much product as possible. And I’m convinced they would sell healthy versions of their products if they could. They’d be thrilled. But they’re more hooked than we are on making stuff that’s cheap and convenient and buzzes the brain.

Do you mean they would sell healthy food if there was sufficient demand, so the fault actually lies with us?

I lay the blame on them as well. Having shaped our eating habits and dictated to us for so long what we should value in food, they’re now thinking, “We’re not going to make this healthy thing because nobody’s going to buy it.” People can’t just turn on a dime and eat yogurt without sugar in it. But for me, the most difficult part of writing Hooked was this: Having made it my mission to torment the food companies, I had to acknowledge that to some extent we’re unwitting co-conspirators in this problem, because our biology draws us to their food. So we’re part of that equation, too.

Given my own focus on kids and food, I was especially interested in your discussion of the early childhood food memories in both shaping and fueling our lifelong cravings. Today’s kids are inundated with ultra-processed food, so the implications are troubling.

I’m sympathetic to some food addiction scientists who tell me they don’t even watch TV or allow a television in their house, knowing how influential those advertisements are in shaping their kids’ habits and also their own. And memory is everything when it comes to shaping our habits. It’s one of the ways food is more problematic than drugs, because our food memories start getting planted at an incredibly early age, maybe even in the womb. Compared to drugs, which affect us in our late teens through mid-20s, food memories last a lifetime. And companies are so cunning at knowing how to shape and implant those memories by associating their products with good times. That’s why Coke went into sports stadiums, knowing they could put a soda in the hands of a kid when they’re with their parents at this joyous moment. Through that memory, you will forever associate soda with comfort and joy and family.

Another question about kids: You mention that in teens’ brains, there’s this push-pull between the allure of processed food and what they know about nutrition and health. But are they actually getting meaningful nutrition education—and isn’t it drowned out by aggressive food marketing at any rate?

That’s a really good question. Even when I did that little experiment for the Times, where I got an ad agency to create advertising for broccoli, their very first decision was [to] in no way tell people broccoli is good for them, because the government’s been pitching that for decades, with no response on our part. I think the challenge is finding ways to tap into that [health message] without hammering kids, because they’ll run away from that kind of pitch.

I’m reminded of a study where teens learned about food industry tactics—in fact, I think they read an excerpt from your last book, Salt Sugar Fat—and it actually improved their food choices.

That’s what I meant by home economics. There are programs where they’re teaching kids to shop and plan and cook, but also to think about food in a political sense: Do you want these multinational companies telling you what you value in food, or do you want to decide for yourself? That’s a political framing of food that’s very powerful, even with younger kids. I’ve given talks to middle school kids, and they totally get that.

Let’s talk for a minute about food pricing. We might think food bargains appeal to us on an intellectual level, but you claim there’s a biological imperative that draws us to lower priced food. Can you unpack that for us?

Evolutionary biologists pointed out to me that one of the things that defines us is our ability to save energy. When we were in hunter-gatherer societies, instead of chasing down an impala for dinner, it made much more sense to grab that aardvark sitting there that can’t run away—it’s a sort of a cheapness that’s defined as “less energy expenditure.” Through natural selection, we became attuned to getting things that require less energy, and that now includes the money we have to earn through expending energy at work. So, while we like to think that we’re shopping for health or brands or whatever, cheapness is right up there on the list. That’s why there are these big new box-store chains selling food at lower prices than even Walmart, and in the parking lot there are all these luxury vehicles. Everybody gets excited when a box of toaster pastries costs 10 cents less. It is just an instinct, one of our natural addictions.

Let’s end on a positive note. Even though it feels like we’re outgunned by the industry, you believe we can “reverse engineer” our dependence on processed food. Tell us how.

I’ve really become enamored with this idea of turning the tables on the companies, by taking back stuff they stole from us. I came to realize they didn’t invent any of these things they’re now using against us, including salt, sugar, and fat, or cheapness, convenience, and variety. Those were all things we had when we were still eating well, and they took those things and corrupted them.

To take a tiny example, long before there were sugary sodas, there was seltzer. And one of the reasons why there was seltzer is because the bubbles themselves seem to excite the brain almost as much as sugar. And so in my house, even my 16-year-old has been able to shift from drinking soda to drinking plain seltzer, and he’s satisfied enough by the bubbles to resist the temptation of soda.

Or let’s take convenience. They so oversold us on the idea of these packaged foods being convenient that we forgot that we can walk into the spaghetti aisle, grab a can of plain plum tomatoes, and bring it home and make a quick sauce. I mean, I’ve got spaghetti sauce down to 93 seconds.

Politically, it’s just really empowering to think of taking stuff back that these companies took from us. It’s a theme that can really work in our personal lives.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.