Mark Kurlansky’s new book traces the ways economic development threatens salmon—and what that pattern means for humanity’s survival.

Mark Kurlansky’s new book traces the ways economic development threatens salmon—and what that pattern means for humanity’s survival.

March 5, 2020

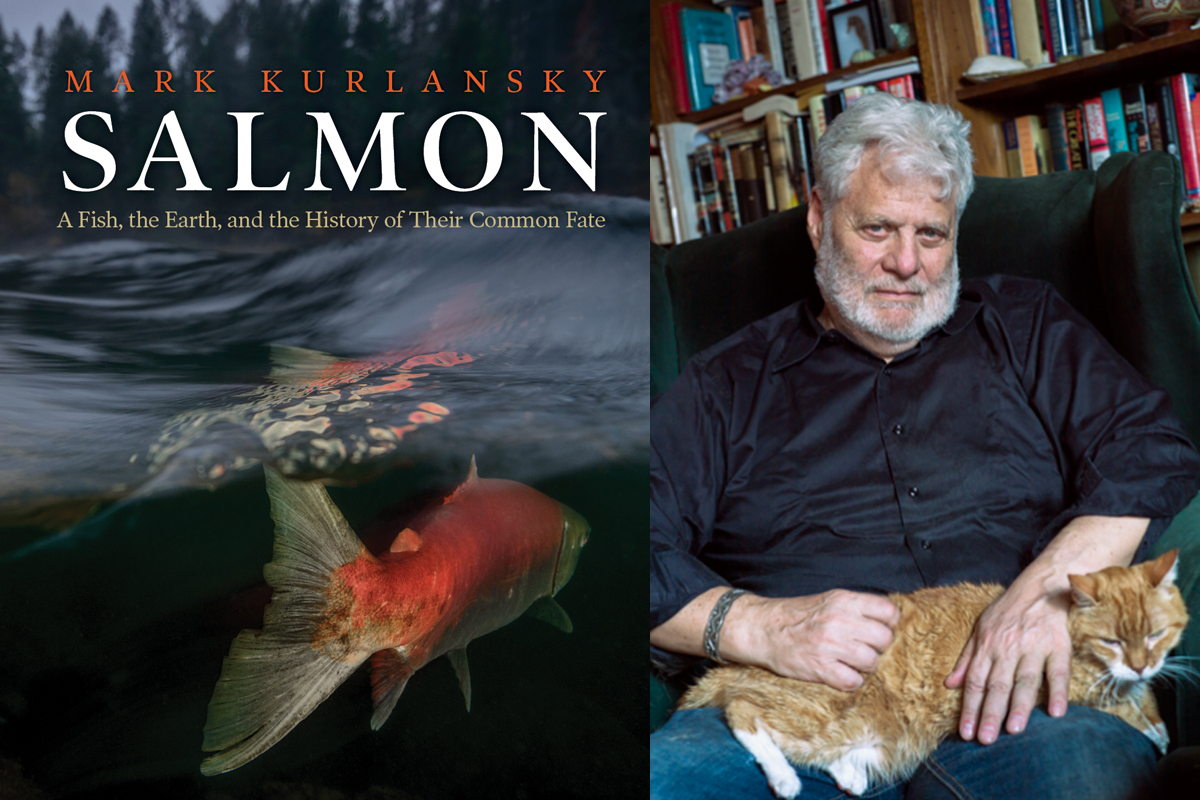

Mark Kurlansky has been telling the story of how humans eat, one food at a time over the last 20 years. He has published popular books including Cod, Salt, and Milk, but his 33rd book is written with a new sense of urgency.

“Of all the things that I’ve looked at over the years, I’ve never run across anything that I found scarier than the fact that the oceans are losing their carrying capacity, that the ocean is losing its ability to feed fish. That’s another way of saying that the planet is losing its ability to sustain itself,” he said. “Salmon is one avenue to talk about that.

Salmon: A Fish, the Earth, and the History of Their Common Fate, released this week, includes a fascinating account of how these unique creatures live, sometimes navigating hundreds of miles back to their place of birth to spawn while leaping waterfalls and actively changing the color of their bodies.

“It’s just one of the most incredible animals in the animal kingdom. It’s extremely beautiful and has this incredible lifecycle that sounds like it was written by a Greek tragedy writer,” he said.

Unfortunately, given its ubiquity on plates around the world, the bulk of the narrative relates to how humans have been amplifying that tragedy for centuries, threatening the existence of salmon both by eating it and also by destroying its habitats with dams, water pollution, and now ocean acidification caused by climate change.

Kurlansky spoke with Civil Eats about how the environmental destruction wrought by commercial enterprise has decimated salmon populations worldwide, and why that matters for all inhabitants of this planet.

You covered cod and oysters before. Why salmon, and why now?

When I wrote Cod [which was published in 1999], people were really just beginning to talk about fishery management and overfishing. The Grand Banks had just collapsed, and people became very focused on this issue of overfishing. And as I followed cod and other fish through the years, I came to realize that there was a lot more involved. Why was it that, although they closed down the Grand Banks and severely curtailed fishing in the Gulf of Maine, cod still weren’t doing well?

“All you really have to do to save salmon is save the earth.”

With salmon, I saw an example of a fish that had so much going on aside from fishery management, which historically was a big issue, but in our times isn’t that much of an issue. Because if you try, it’s pretty easy to manage a salmon fishery, because they’re very predictable. So it should be a problem solved, but it’s not. There’s pollution, bad farming practices, urban sprawl, deforestation, dams, and especially, climate change. I started to realize that everything that we’re doing wrong with the planet is being done to salmon. So all you really have to do to save salmon is save the earth.

Darwin talked about how every time you lose a species, you endanger other species—the whole concept of biodiversity. Salmon is an extreme example. There are just so many species that are dependent on salmon. The whole life of those rivers depends on salmon.

The issue I found to be most complicated is dams. Because they’re a source of power that can help move us away from fossil fuels, but at the same time, they destroy salmon.

I mean, they destroy rivers. In countries like Sweden, they thought they were doing a great thing moving away from all these bad energy sources to hydroelectric. They’ve now been rethinking that. It’s tough. What you end up realizing is that what really needs to be rethought is our whole notion of economic development. Most of the things that were done to develop the economy are bad for the planet, and so, in the long run, actually bad for the economy.

I had this kind of revelation. We’re looking at the history of salmon and how in England, in the British Isles, the rivers were completely destroyed by industry by pollution and dams that were used for energy to power factories, so that eventually the rivers were completely dead. And then it was basically British people who came to New England and did the exact same thing. And it was New Englanders that went to the Pacific Northwest and did it again. So I was thinking, why don’t they ever learn?

And then I realized: Because they don’t regret what they did. It was it was their goal. Britain created the most powerful industrial economy in the world. New England became the most prosperous industrial economy in North America. And by damming the Columbia River and creating an abundance of energy, they developed a huge economy in the Pacific Northwest where before there had been none. So these are actually great success stories, except that they’re destroying the planet.

I’m not saying that we shouldn’t have economic development, but we should be asking ourselves: Is this a good way to be developing?

And then when people try to address the decline in salmon, it often doesn’t work. It seems like you concluded, for example, that hatcheries have basically been a failure.

By and large, yes, with some exceptions. The original idea of hatcheries was: “Oh, you know, we can do all of these destructive things, and we’ll still have fish because we can just keep making more [in fisheries].” But if the environment is no longer suitable for the fish, it doesn’t make any difference. If you produce more, they won’t do well.

I’m mystified by places like Alaska. Why do they have hatcheries at all? They have a successful fish stock and they’re doing quite well. In the case of something like restoring the Penobscot in Maine, I do understand it because they’re not able to get enough wild fish to spawn in the river and to return to it, and they need some sort of help.

It’s a very tricky issue. With most environmental issues, you have the science on one side and you have the profit-hungry business on the other side. With hatcheries, there really isn’t that much of a profit motive on any side. It’s just a disagreement between scientists. I think the overwhelming majority of scientists are anti-hatchery, but not all, and the ones who aren’t can show you a few incidences where hatcheries have helped.

It’s also clear that hatcheries aren’t going to give you the solution. The solution is to completely change the way we do things: To use alternate energy and not hydroelectric and not fossil fuels and be much more careful about farming practices and building and urban development.

What about farming salmon? Did you come across any examples of companies doing it in a way that seemed sustainable?

Salmon farms come with problems. If you take [salmon] away from the ocean and you have them in enclosed pens [on land], you solved the problem of sea lice and escapes. Those are two very big problems. But you’re also creating problems. Fish farming inland has a big carbon imprint, so that’s not the direction you really want to go, or maybe it is, but you need to figure out a better way of doing it.

I was very opposed to fish farming in my cod book and earlier. I still think it’s very harmful, but I think that we need to figure out how to make it work. Creating protein from the ocean at a low cost is a great idea. You know, the Scandinavians thought they were going to create this protein from the ocean, and it was going to all be sustainable. First of all, it’s unsustainable because they had to feed the fish wild fish. They made some progress with that problem, although it turns out that farmed salmon tastes a lot better when it eats fish.

Isn’t it possible that salmon just isn’t the right fish to farm because of its size and diet?

Good point. There are vegetarian fish like tilapia, which are much easier. I mean, salmon is a voracious carnivore. That’s a problem. But on the other hand, there are advantages to farming salmon. The guy I dedicated the book to, Orri Vigfússon, who spent his life trying to save salmon, once said to me, “You know, we would never have been able to buy out all these fisheries and stop this fishing if these societies didn’t have farmed salmon.”

For example, Scotland or Norway, those cultures are very centered on eating salmon, and the only salmon available is farmed. And people aren’t unhappy about it because they recognize that by not eating wild salmon, they’re trying to save the salmon. But if it meant never being able to eat salmon anymore, that would be a more difficult decision.

But given the state of things, is that kind of difficult decision necessary? Should humans be eating salmon at all?

We could ask that question, but I think the more useful to ask is: Should humans drive cars? There’s so much that we’re doing that’s bad. Why pick on the salmon?

The point that I’m making is that we have to take on the issue of carbon in a much more basic way. Really changing the way we live on the planet and eliminating fossil fuels, which we could do, would be a good start. It’s quite remarkable to think that if you were in Indiana and you’re driving a car and emitting carbon, about a third of that carbon is going end up in the ocean. It turns out that carbon dioxide is very attracted to water. So it’s our whole lifestyle—even if we don’t live near the ocean—that is killing the ocean. Not eating salmon just doesn’t strike me as taking on the issue head on.

Author photo © Sylvia Plachy.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.