In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

August 19, 2021

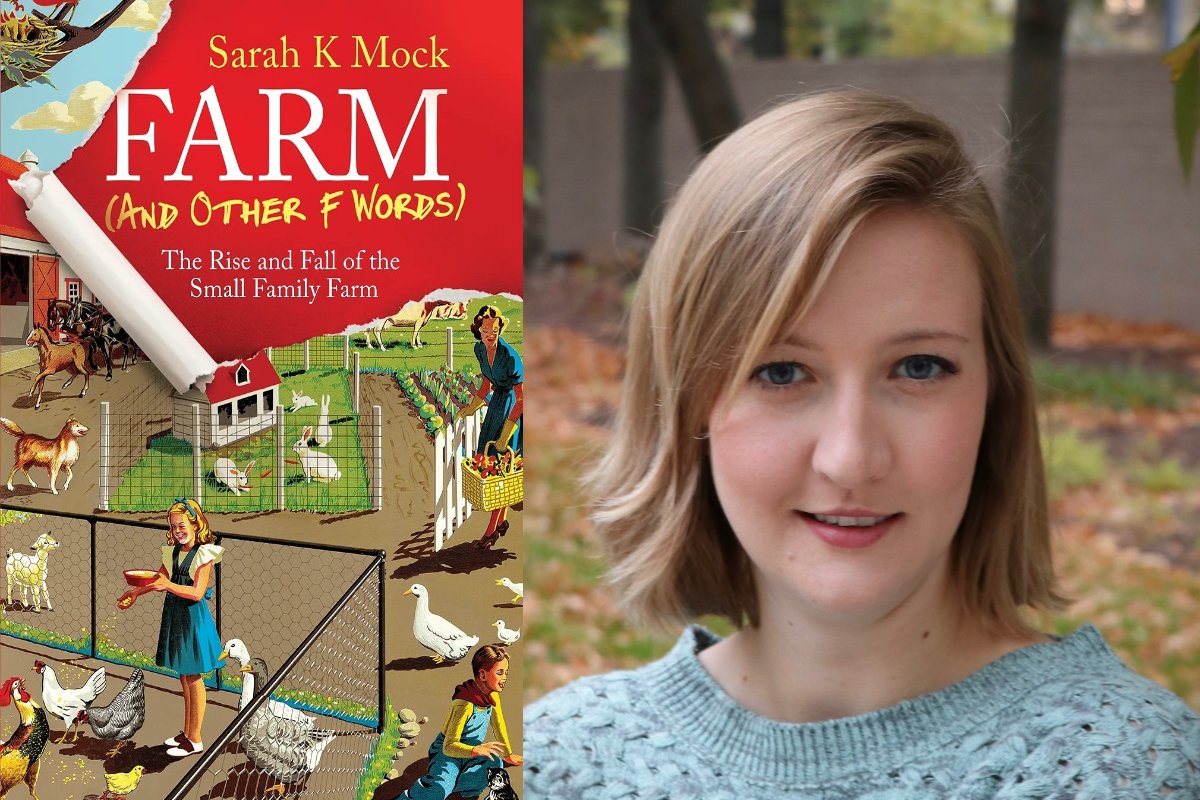

Sarah Mock is the author of the provocative book FARM (And Other F Words): The Rise and Fall of the Small Family Farm, released in April. Although the cover depicts a colorful, storybook image of farm life, readers will not find within another chronicle of pastoral bliss achieved through sweat equity.

Instead, chapter by chapter, Mock argues that the ideals of the farm-to-table movement are largely built on a fiction. Today’s small farms, she asserts, are not the ideal social, economic, or environmental model for truly sustainable agriculture.

As an independent agricultural reporter critical of U.S. farming, Mock is accustomed to riling up conventional farmers on Twitter. But she’s been surprised how the ideas in her self-published book have ticked off some advocates who believe that supporting small farms is the answer to the food system’s failures. “They cannot hear that maybe the narrative is a little bit more complex than they think,” she told Civil Eats.

At 28 years old, Mock is more than qualified for this work. She grew up on a farm near Cheyenne, Wyoming and raised dairy goats—her own failed small farms venture. Just out of high school in 2011, Mock got a job with the grasshopper program at the regional U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) office. While a student at Georgetown University, she worked on economic development projects in South Africa, India, and Burkina Faso. After graduation, Mock volunteered with Worldwide Opportunities in Organic Farms (WWOOF) in California, where she learned about farm labor abuse firsthand. Next up, she spent time in Silicon Valley hustling for two startups, OnFarm (now defunct) and the Farmers Business Network, while writing an ag policy blog on the side.

In early 2017, RFD-TV, a national television network covering rural issues, recruited Mock to report on U.S. farm legislation and trade policy from within the USDA offices in Washington, D.C. She started work on the same day as Sonny Perdue, the Secretary of Agriculture for the Trump administration. Mock spent three years covering congressional agriculture committee hearings before going freelance in 2019. She weaves all of these experiences into FARM (And Other F Words) along with deep reporting and thought-provoking takeaways.

Earlier this summer, Civil Eats spoke with Mock about what most people get wrong about small farms, the link between land and wealth, and the model for sustainable, equitable, and profitable farming operations she calls “Big Team Farm”—a notion that expands what makes a farm beyond the family and into something between a collective and the community.

You write articles and produce other content that challenges people’s conceptions about farming, and your tagline is, “Not a cheerleader, not the enemy.” Can you tell me about that?

A lot of people in agriculture are like, “We have to stick together.” It starts with kids when they join 4H, then Future Farmers of America (FFA), and no matter whether you’re a producer, in policy, or in the media, we all have to be advocates—agvocates. And that is not a healthy mindset. Criticism is not hate. Conflict is not abuse. A lot of people in ag think of themselves as cheerleaders for the industry. As soon as you start expressing skepticism, you immediately become the enemy. I’m just here to ask some hard questions and have a meaningful discourse.

Can you lay out the premise of FARM (and Other F Words)?

This book follows my own journey of trying to understand what farms are. I knew all these old, conventional farmers who were doing quite well. And I knew all these other farmers who were trying really, really, really hard [to do] all the things we love: They were small, community-focused, cared about environmental health, and they weren’t trying to get rich. And they were all going out of business.

The original idea for the book was: what can these old, established farmers teach these young farmers—is there some way to bring these two things together? Can we have progressive, economically successful farms?

I spent a year with the Mills family, a 16th-generation farmer in Virginia, and I also spent time with Chris Newman [owner of Sylvanaqua Farms] who was that young hustling farmer. And the more time I spent with [them], I was just like, “These farms look nothing alike. I don’t understand what one would teach the other because they’re not even playing the same game.”

And I was like, “What if it was just not the way we thought? What if it’s not like, ‘small farmers are the best and they used to work and they just don’t anymore because industry destroyed them?’” And so, I came to a whole bunch of new conclusions.

What is wrong with our beliefs about small farms?

Our idea of the small family farm is very idyllic. It’s like a Dutch oil painting of a farmhouse and a beautiful landscape. It’s truly amazing to think that colonists in 1600 had the same idea of what a small family farm is in their imaginations as we do today.

From an economic perspective, that whole model never worked. There’s a trade-off in agriculture between land and labor, right? You have to have X amount of labor to be able to work a certain amount of land. And for colonists in North America, land was about speculation from the very beginning. That’s why there was a lot of starvation amongst early European communities, because they weren’t growing food crops; they were growing tobacco and cotton.

Agriculture in America was always a get-rich-quick scheme. And it was partially about producing high-value crops and partially about just holding the land until it appreciated enough in value. And that is not part of our idyllic perception of the family farm.

In the book, you redefine farming as a real estate business overlaid with a food production business. Can you explain?

Farmland has outperformed the S&P 500 for [most of] the last 50 years. It’s better than a stock portfolio if you can get it, hold it, and not pay taxes on it. In states like New Jersey, you only have to make $500 a year on your farm for it to be [designated as] a farm. So, it’s a very loose definition.

We tend to focus, especially in the food movement, on the folks at the farmers’ market who say, “I’m renting land. I’m barely getting by.” [Only] 10 percent of farmers in the U.S. are full tenants [and the rest own at least part of their land]. Owning farmland is why 2 million farmers in the U.S. own $3 trillion. It is a tremendous asset. So that’s the real estate business.

On the other side, you have the production business, which everyone thinks is the only business that farmers have. You can divide production businesses into farmers who actually grow food and farmers who grow all of the non-food grain [corn and soybeans]. Food production agriculture is one of the least lucrative things you can do on land. So, when you are 70 years old and you need to hold [on to] 5,000 acres, the easiest thing to do is to plant it all in corn because you get paid by the USDA.

When you looked at the whole ag landscape, did you find that land ownership and the wealth in that land is the great differentiator between farms, or is that simplifying too much?

Land wealth is a huge thing. And it’s something that no one ever wants to talk about. Of all the things that I can talk about in ag, [it’s] the one that gets me the most personal safety threats [on social media as well as occasionally in-person].

In the spring [2021], you were working on contract with Sylvanaqua Farm when there was a messy, public fallout between the owners and the BIPOC employees over critical labor and leadership problems, and you subsequently left the business. Could you talk about what happened and what lessons you learned for building the ideal farm business model?

I published a letter about what happened at the end, but I’m happy to talk about it. It was really heartbreaking. In early 2020, Chris was making a transition from being a small family farm operating in a way that is very old school to setting up a [worker-owned] collective.

It’s really hard to build in collective ideals after something starts. If it’s not an inherent part of the leader’s vision, it’s really hard to wedge that in afterwards. In a lot of businesses, small farms and small food businesses, the visionary tries to be the manager and also the technician. And it takes a very special kind of visionary to realize that you need a separate manager with commensurate power and authority. There needs to be systems to make sure that people have a voice and buy-in.

Chris is still farming. Sylvanaqua still exists. And hopefully he gets a chance to try and build something a little different and do it from a place of wisdom. I talked to a lot of folks right after I left who were very disappointed. And in my mind a failure isn’t an indictment of the idea. Seeing what happened there and taking a step back was a good reminder that like every geography, every crop, every market, every community is going to have a solution that is unique to them so that it works just right in their situation.

You don’t have to build a collective from day one with exactly the right people. There are people who find ways for their employees to participate in a meaningful way and have a voice that doesn’t involve ownership or management. They still have a traditional management style and they’re still running food and farm businesses that respect their dignity and is economically viable. That is the trinity: good jobs, good environmental outcomes, good food. There are a million ways to build a good farm and to build a good Big Team Farm.

What is your jumping off point for presenting a blueprint for Big Team Farm in your next book?

At the very end of [FARM and other F Words], I talk about the history of farming in North America and the Indigenous roots of a common system of collective farming. Whether it’s Asian American, African American, Indigenous, or Hispanic communities—they have all had collective farming in the commons. As a matter of fact, so did Europeans.

We feel like this idea [independent, small family farms] came from the dawn of time, but we invented it 400 years ago. For much of human history, we farmed in a very different way. So, I started from the idea, what if we farmed together at a landscape level with a focus on environmentalism?

It doesn’t matter how regeneratively you farm your one acre if your neighbors don’t. The landscape is the landscape, and it sure doesn’t care about your property line. Water flows, air moves, soil blows in the wind, pollen migrates. If the only way to manage in a truly environmentally friendly way is to manage whole landscapes together, that means you have to have a lot of people involved. And the only way for people to work together and appropriately compensate labor is for them to have some kind of shared collective ownership or at least [shared] decision-making.

I found these examples throughout history of people who did these kinds of Big Team Farm models. If someone wanted to do this today, what would that look like? How would you start, understanding that there are few land commons in the United States? But the thing is, you don’t have to sell farmland to pay your employees. You can give away equity. You can use your farmland to leverage compensation.

I talked to a farmer who sells his produce in L.A., and he was the first farmer who ever told me, “I can’t afford $15-an-hour salespeople, and I can’t not afford $25-an-hour salespeople.” You just get much better employees if you invest in them and give them buy in and let them help make decisions. And that mindset has been transformative for him. So, I think it is exciting to see people start to think differently.

The most important element of a Big Team Farm is the recognition that the family is the wrong economic unit for the farm. You and your partner and your five-year-old and eight-year-old are not the full team of people to run your complex business.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

appreciated Sarah Mock's wisdom. And I too hope that Chris Newman and is agricultural philosophy survive. Thank you civil eats for your service to informing us about important issues.

Hi Naomi,

I have some concerns about the recent article on Sarah Mock in Civil Eats, entitled "Agriculture Reporter Sarah Mock Is Challenging the Narrative About Small Family Farms." I think its inaccurate to refer to Mock as an agriculture reporter. She has no apparent reporting experience, as far as I can tell. She comments on Twitter, has self-published articles on Medium, and is self-publishing (essentially, through New Degree Press - which is a pay to play type publisher) a book. My concern is that her writing has no fact-checking and no editor, and some of her statements are wrong. By billing her as a "reporter" Civil Eats seems to be elevating her comments, which I find worrying because not only has she not published with anyone - and thus been fact checked - but she makes statements that, in their inaccuracy, send misinformation out into the world, and threaten the work many, many people have done to develop ecological and racial justice. For myself, I operate a small business based on selling the wool from farms and ranches that operate under a Carbon Farm Plan. Mock's statements in her self-published article on Medium say of Carbon Farm Plans "The problem with just about every “carbon farming” program I’ve look at is, not a one is actively encouraging the long term planting of perennial crops (trees, bushes, and perennial grasses), which is one of the most important elements of sequestering carbon in any landscape." The idea that no carbon farming encourages perennials is flat out incorrect. Every single Carbon Farm Plan from the farms I source from include practices that actively encourage long term planting of perennials. I note these practices on my website. And of the many (35 or so) NRCS practices available for incorporation in CFPs, there are ample practices that plant perennials, such as hedgerows, windbreaks, silvopasture, riparian restoration. How on earth Mock was able to find a CFP or carbon farming program that did not have these practices is incredible. And questionable. Perennials incorporated into carbon farming was literally reported on in Civil Eats: https://civileats.com/2016/03/16/how-carbon-farming-reverse-climate-change-eric-toensmeier/

Yet, when I reached out to Mock to bring up the inaccuracy with this statement, she did not respond. And because her article is self-published, there is no editor or board to bring these concerns to. And now Civil Eats is referring to her as a reporter. I'm left with the uncomfortable feeling that this misinformation might now be validated and the public will distrust the carbon farming efforts that so many people - farms, businesses, non-profits, even institutions like NRCS and RCDs - have gone to to not only make carbon farming valid, but to make it market-ready.

Please take these concerns into consideration. Although Sarah Mock may be an agriculture commentator, she's not a reporter. And the way she is handed the mic to speak about Sylvanaqua Farm (which continues to be a successful farming operation, unlike her one failed dairy goat attempt) has worryingly racist tones to it -- how is it that an unsuccessful-at-farming white person is able to make disparaging comments on a successful BIPOC-led farm with no option to hear the other side? Its surprising coming from Civil Eats.

With respect,

Marie Hoff

Her response:

Dear Marie,

Thank you for your note and your point of view. Your concerns are important to us, however, all of which you state below is not the focus of the Civil Eats' Q&A, and does not merit a retraction or a correction.

While we understand your disagreement with Sarah’s writing and statements made in other media, we respectfully disagree with you about the need to correct this piece or her stature as a reporter (she has worked as such for media outlets, including as Washington correspondent and bureau chief at RFD-TV, Farm + Dairy, Daily Yonder, the Guardian, and more.).

Like all media outlets, the opinions of the people we interview don't necessarily represent the opinions of our editors, and while we interview a variety of people and cover many topics, not everyone agrees with those subjects or topics.

That being said, we encourage you to post a comment at the end of the story—those are publicly viewable and can start a conversation around the points you bring up.

Regards, ns

My final comments: I'm curious as to why Mock's reporting experience wasn't noted in the beginning when the writer is trying to establish her validity? Instead, things like a failed dairy goat venture and wwoofing in CA (which isn't legal except in a few rare circumstances) are. This reporting experience also did not come up when I searched for Mock online, just her self-published articles. The editor's response also does not address my concerns about the racism inherent in giving the mic to a white person to disparage her former BIPOC employer ("hopefully he gets a chance to try and build something a little different and do it from a place of wisdom" -- that's a burn), without letting him represent his side of the story or defend himself from such belittling comments.