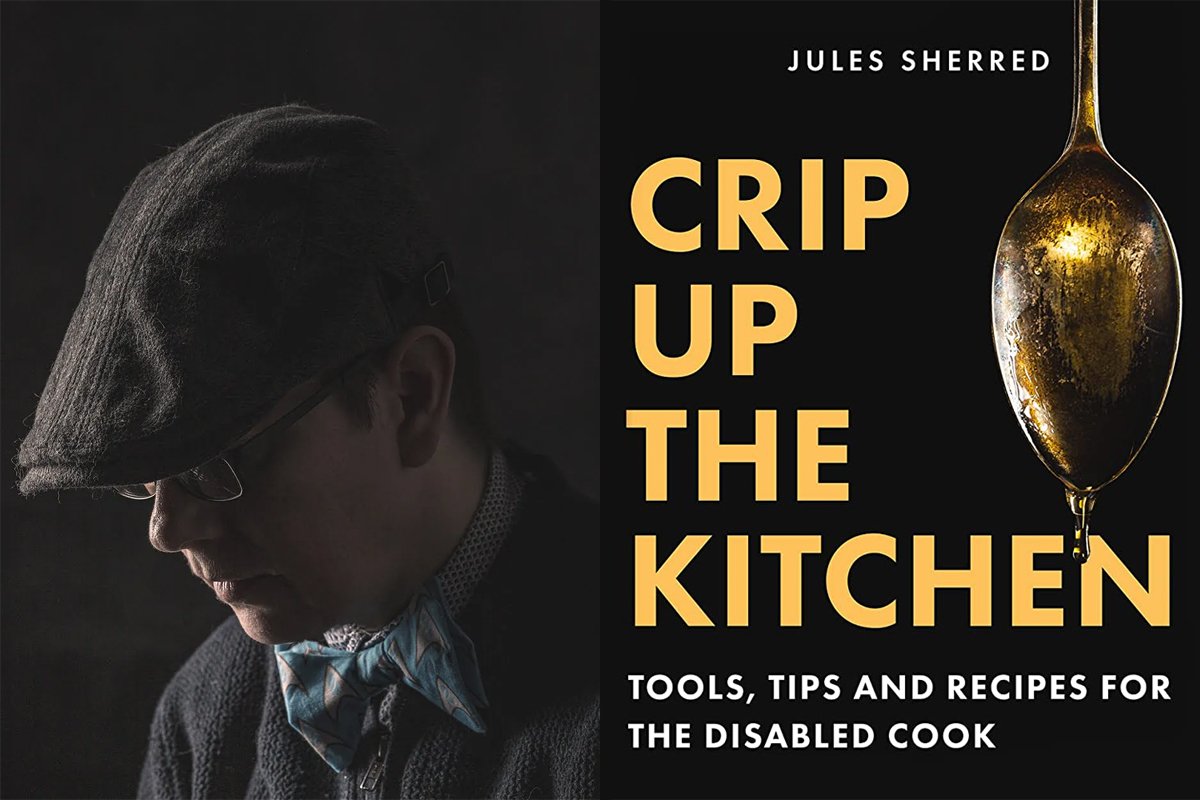

Jules Sherred’s book ‘Crip Up the Kitchen’ offers recipes and acceptance in ‘the worst room’ in the house for people with disabilities.

Jules Sherred’s book ‘Crip Up the Kitchen’ offers recipes and acceptance in ‘the worst room’ in the house for people with disabilities.

June 13, 2023

Jules Sherred’s Crip Up the Kitchen is an unusual cookbook: It foregrounds the needs of disabled cooks with disability-friendly recipe development and tips on building out safe and enjoyable kitchens to cook in. It also explores the complexities of food, especially for immigrant communities who may have difficulty accessing ingredients or may struggle with negative social attitudes about beloved dishes.

As a disabled person who has experienced inaccessibility in the kitchen firsthand, Sherred—who lives in a household of neurodivergent people, himself included—has had to learn to navigate the kitchen in a wheelchair and with hand disabilities as his body has changed over time.

Sherred, who works as a food and lifestyle photographer, recipe developer, and journalist, produced the lush photography throughout the book. As a disability advocate as well, he was inspired to create this resource as part of his search for more disability representation in the kitchen and home garden. As a trans man, Sherred is also active in trans advocacy, including in response to conversion therapy.

“At a minimum, 25 percent of people are or will become disabled. And that’s the people who are willing to admit that they are disabled.”

It’s not all about eating, he says of the text. “I want to give [readers] some food for thought about the violence behind a lot of the food we eat,” Sherred said in a conversation with Civil Eats. He notes that while his home city of Duncan, British Columbia, is the “sixth-most expensive place to live in British Columbia,” it also has an incredibly high poverty rate, particularly in the Indigenous community.

Even as Sherred celebrates vibrant flavors, he acknowledges that cooking should also include thinking about food politics, such as Indigenous people being deprived of culturally appropriate foods.

The politics of the book also include personal body politics for a community that often feels unseen and unheard, especially in the kitchen, where hostile attitudes can make members feel unwelcome for using pre-chopped vegetables, specialty kitchen implements, and simplified recipes. For Sherred, accessibility is a priority as he adapts recipes to make them easier to read and discusses common dietary issues, meal planning, and how to decide which resources are most effective for his readers’ individual needs. “I want people to feel heard and seen and accepted,” he said.

Much of Crip Up the Kitchen draws upon immigrant culinary traditions thanks to the neighborhood where Sherred grew up and the Punjabi family that “adopted” him in his teens. Though he has Eastern European and British roots, the cookbook has a heavy focus on Thai and Punjabi food, with the goal of making these recipes more accessible to cooks who want flexible options.

For Sherred, a turning point was his introduction to an electric pressure cooker, which revolutionized the way he thought about cooking. This implement, plus the air fryer and bread machine, are the cornerstones of this text. Recipes include classic daal, a paneer recipe for those who want to make cheese at home, Thai green curry with chicken, and even an air fryer chocolate cake, all designed to be flexible and adaptable for disabled cooks (for example, leaving out chilis if a recipe is too spicy or swapping vegetables to accommodate dietary needs).

“Sharing is love,” he says. “Cooking for somebody is an act of love. This is an act of love. Here are my recipes . . . Let’s see each other.”

In your introduction, you talk about the kitchen as the “worst room.” Can you say more about that?

Because nothing about it is conducive to cooking when you’re disabled! Whether that be a physical disability, or some type of neurodivergence that makes navigating the [kitchen] “work triangle” difficult.

A really good example is my kitchen. I’m a wheelchair user. Counter heights [are hard], and even before I was a wheelchair user, I’m also a short lad. Unless you’re 5’6” or over, counters are not ergonomically built. It’s a literal pain in the wrists to be preparing at counters.

“I tried to include as many voices as possible and did my best to think of solutions for them.”

Even in my wheelchair, there’s technically enough room between the fridge and counter for [the building] code, but it’s really difficult to navigate safely around that corner. If I’m in my wheelchair and want to open the fridge, that’s impossible, because there’s no room. Even things like the distance to the stove, and the sink, and the fridge, it’s all now done for aesthetics instead of actual function. If you’re able-bodied, it makes no difference. If you’re somebody who’s disabled and has to use mobility aids in the kitchen, it’s unsafe.

Some people might not have the ability to work at a dining room table or an in-kitchen table, [which is] my recommendation [for people who can’t work in the kitchen]. Doing it on your lap is no bueno. That’s super dangerous. But [some people] have no choice—it’s either that or they don’t eat.

It can be really tough to find cookbooks and guidance targeted at disabled cooks. Why?

At a minimum, 25 percent of people are or will become disabled. And that’s the people who are willing to admit that they are disabled. I have a book launch event on Saturday, and one of my questions is, “Do you need any accommodations?” And there are so many people who say, “I’m able bodied, except for this, this, and this.” But they still consider themselves able bodied because society has made being disabled such a dirty thing. You are not [seen as] a whole person. You are less then. Ew! Like being dead is better than being disabled in a lot of people’s minds. Why would you want to make accommodations for something that is so gross and icky? If you have other experiences of marginalization, then that otherness is even more compounded.

It’s slowly starting to change, but 99.99 percent of stuff that is available is written by able-bodied people through a lens of trying to make a disabled person fit into an able-bodied box.

It is interesting that you mention accommodations, since that’s a real challenge for a lot of disabled people.

When I’m meeting with clients [in my capacity as a disability advocate focused on inclusion], I give specific examples, like I’m autistic and I need to take a 10-minute timeout every hour so I don’t melt down, because I get overstimulated. And I also have a spinal cord tumor and have to [take breaks often] so that the pain doesn’t become blinding. When I disclose, it makes it safer for other people to disclose, I find.

There’s also always danger in disclosing, for a lot of different reasons. There are times when it’s not necessarily possible; it’s always a tricky balance to do it in a way that is safe [for everyone].

When it comes to the kitchen, people tend to dunk on “uni-taskers” and other “unnecessary” kitchen equipment that is actually beneficial for disabled cooks. What are some examples that you find helpful, other than the electric pressure cooker?

There was over a year when I could not use my hands at all while I was waiting for my thumbs to be operated on. Imagine not having opposable thumbs and having to cook for yourself! [A reader] suggested an egg slicer can be used for soft things like strawberries, grapes, mushrooms, and cantaloupe. I was like, that is genius! You want the one that has the types of different shapes; the multi-egg slicer slices and juliennes.

Another is the three-in-one peeler, corer, slicer. A lot of people think to only use those for apples. I like to use them for potatoes, pears, anything that needs to be peeled and sliced. So they’re spiral-y. It makes no difference.

“I’ve been very pleasantly surprised by how many able-bodied people have said, ‘Wow, I cannot use this, but I know somebody who can—these suggestions are great.'”

I also like to use a pasta roller for rolling out pie crusts and making roti and flatbread and stuff like that.

You have a comprehensive list of recommended kitchen equipment and nice-to-haves. It’s pretty spendy, especially for a community with a high poverty rate. Are there items you think cooks should start with?

The major thing to start with is the electric pressure cooker. It’s the most versatile. If you cannot safely use your stove or your oven, you can use that. The great thing is that you can also use it anywhere in your home—in a small dining area, or even in your living room, where you can stick it on your coffee table. Do all your prep at your coffee table, put it in your pressure cooker, and you don’t have to worry about burning down your house. It’s amazing!

Then you also need something that works for you for chopping. The first big thing that I got for that was a very, very versatile and inexpensive immersion blender with attachments. It had a whisk, a food processor, beaters—so it had attachments that basically were four different appliances in one. You can’t do as much chopping, but it’s still better than spending $300 on all those appliances separately.

And then a really good nonslip cutting board and a decent chef’s knife. The lightest little bit of pressure is going to slice through.

Those are the basics to start with, and you can do most of your prep with those.

How did you approach recipe development and documenting how to modify recipes and outfit a kitchen?

On my website, Disabled Kitchen and Garden, a lot of my regular readers would test recipes and give feedback. I had a group of recipe testers—I called them beta testers because I come from a coding background—a whole bunch of people with different disabilities, both physical and neurodivergences. They let me know what wasn’t working for them, what was, what they would like to see, and what the common stumbling blocks were. I did a lot of consultation so I had a lot of experiences outside of my own.

I tried to include as many voices as possible and did my best to think of solutions for them. I would present those solutions and have them retest it with those solutions until we found something that worked for the most people. You can’t help everybody—that’s not possible with one book. I went through it with a lens of universal design. I asked myself, “What symptoms do I focus on that are more universal, that can create strategies to help the most people, while still recognizing that all of our experiences are different and we all have different needs?”

I got a lot of feedback from neurodivergent people who said that reading recipes causes their brains to explode. I was able to identify common points of failure in the reading process and make it so those things don’t exist anymore. I included reminders to mise en place, and prep. . . [so cooks] only have to worry about what’s right in front of them at the moment.

How are people responding to the book?

I’ve been very pleasantly surprised by how many able-bodied people have said, “Wow, I cannot use this, but I know somebody who can—these suggestions are great.”

Prior to the book being published and it getting positive press, I remember one time I was sharing a really important family recipe for Doukhobor Borscht on Twitter. There’s a certain pull-yourself-up [mentality that one experiences] growing up in Eastern European cultures that kind of makes you hard. It’s trauma-based. You’re not supposed to complain, you’re not supposed to take shortcuts, because that makes you “lazy.”

I had a few people of Eastern European descent tell me that my baba would be very disappointed in me, that I was taking shortcuts, and the whole joy is in the labor. And I just wanted them to know my baba would be very happy that I am able to enjoy this meal that she cooked for me with love.

“Screw making able people comfortable. Be yourself. My whole entire thing is live authentically.”

There’s so much snobbishness when it comes to food and cooking around what makes you a real cook and what makes you lazy. Unless you’re doing everything from scratch, you’re not a real cook. Unless you’re chopping the garlic, you’re not a real cook. Unless you’re standing over the stove and sweating your face off and putting yourself in pain for five hours, you’re not a real cook. My book specifically says, “No, screw that.” It’s radical.

I also saw people asking, “Is it OK for them to use the word ‘crip?’” And someone said, “Here’s the definition that he has in the book—it’s fine. It’s their word that they’re using in their community to reclaim how it’s been weaponized against disabled people.” There are those discussions too, people who are not disabled trying to police the language that I use. If disabled people want to have a conversation about it and feel the need to call me in for something, I’m more than happy to have a conversation.

What do you want people to come away with as they cook their way through the book?

Screw making able people comfortable. Be yourself. My whole entire thing is live authentically. There is no way I will ever tell somebody to fit themselves in a box that is not theirs. I know that is going to cause some discomfort within the disability community as well, and I’m fine with that. We can have those discussions. But abled people cannot come at me. It is not their place.

I do want able-bodied people to have use of my book. Anything that benefits the most marginalized people benefits all of society. If you’re a busy family that doesn’t have time to cook and meal plan, please use my book! I want everyone to use it.

But if [this cookbook] is not for you right now, you will still benefit [in the future]. Everyone gets sick at some point. We live in the times of COVID—you are one infection away from disability.

I want disabled people especially, though, to be happy. I want them to be seen. That’s why my dedication is to everybody who is not allowed to be seen, who has to hide who they are. I want them to be celebrated and seen and accepted for exactly who they are, no conditions.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.