Agrichemical companies won’t say how they’re disposing of seeds coated with hazardous pesticides, and the EPA isn’t tracking it.

Agrichemical companies won’t say how they’re disposing of seeds coated with hazardous pesticides, and the EPA isn’t tracking it.

April 5, 2022

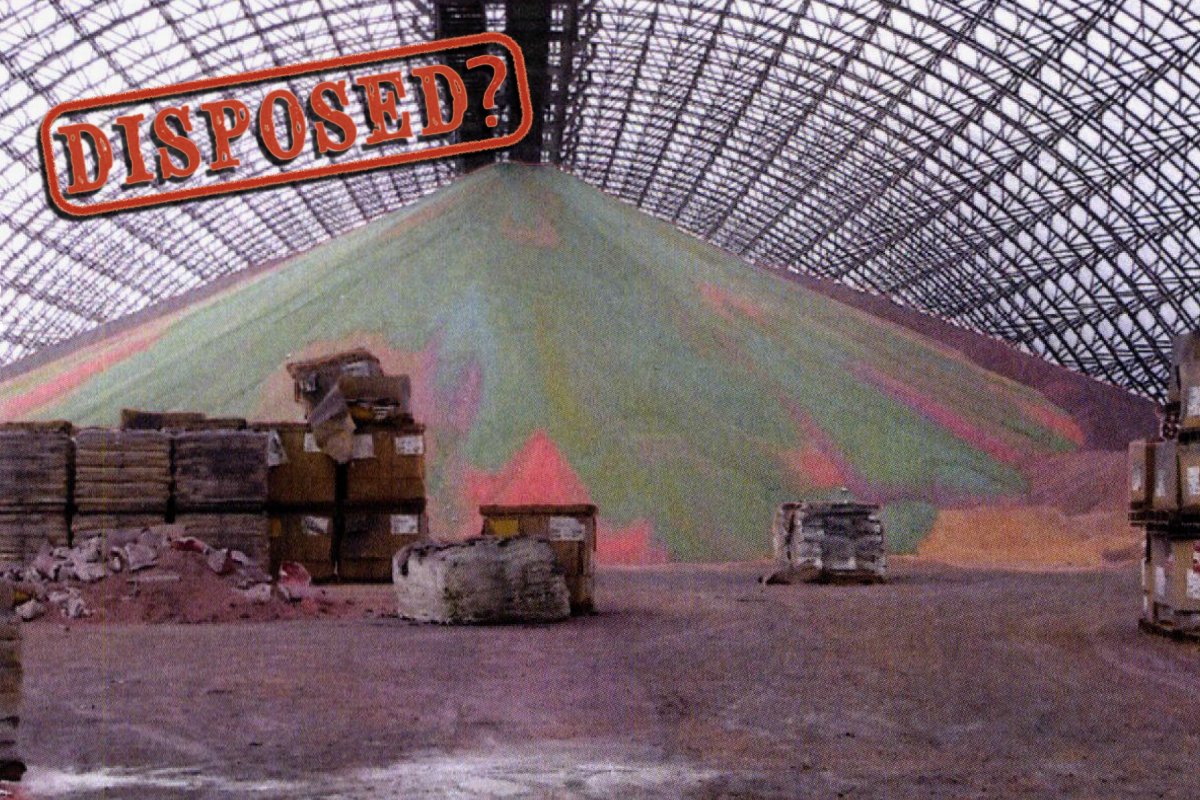

A mountain of pesticide-coated seeds inside the AltEn facility in Mead, Nebraska. (Photo by Jason Windhorst, NDEE)

This article is the first in a new series of in-depth investigations. Got a tip? Please contact us on our secure email at civileats@protonmail.com.

Mark Pomajzl had to step back from the looming pile to capture its height with his Canon PowerShot camera. Its peak pushed against the arched, white roof of the hoop building. Sun streamed in through the plastic, illuminating pink, orange, and purple ridges intersecting swaths of green.

It looked like a life-size version of a volcano a fourth-grader might build for a science fair diorama. In fact, it was a mountain of seeds. In smaller quantities, the seeds would be nearly indistinguishable from candy—rainbow Nerds, specifically—that the same kid might share with friends. But the bright colors served as an eye-catching warning: These seeds have been coated with dangerous pesticides.

Pomajzl discovered the pile at the AltEn ethanol plant in Mead, Nebraska, on August 1, 2018. He and his colleague Jason Holsten from the Nebraska Department of Environment and Energy (NDEE) were conducting an inspection. Earlier in the summer, nearby residents had complained of horrible odors emanating from the property; they believed that something in the air was making people sick. Pomajzl and Holsten were there to investigate.

Three and a half years later, AltEn is now nationally known as the site of an ongoing environmental and public health disaster. For years, AltEn had been processing corn, sorghum, and other seeds—much of it treated with pesticides and fungicides—into ethanol. AltEn sold a byproduct of that process called “wet cake” to farmers to spread on fields as fertilizer. Wet cake from ethanol production is commonly used for that purpose, but most ethanol plants start with field corn, not treated seed.

Wet cake that contains pesticides above certain levels is not supposed to be used on fields, and public documents show the farmers and the Nebraska Department of Agriculture were initially unaware of the levels of pesticide residue in AltEn’s product. When the agency detected the pesticides, it ordered AltEn to stop selling the product.

The larger question of how pesticide-treated seed is being disposed of by agrichemical companies has gone unanswered.

As pesticides from the wet cake polluted the surrounding environment, AltEn’s wastewater also spilled into waterways. Bee colonies have since collapsed. Dogs have gotten sick. A research team at the University of Nebraska is now tracking animal and human exposures, while locals are fighting for answers to fundamental questions about the future long-term impacts on their air, water, and health.

Meanwhile NDEE is overseeing a cleanup led by six companies whose unplanted seed, sent to AltEn, is the original source of the contamination. The group includes the world’s three largest agrichemical giants: Bayer, Corteva Agriscience, and Syngenta, as well as AgReliant Genetics, Beck’s Superior Hybrids, and Winfield Solutions (owned by Land O’Lakes). The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is assisting NDEE and told Civil Eats it is “closely monitoring the situation.” And AltEn faces one lawsuit brought by NDEE and three other lawsuits filed by seed companies seeking reimbursement for the cleanup.

In these photos from the Nebraska Department of Energy and the Environment inspection, blue dust coats the east edge of the north hoop barn at the AltEn facility (left). The inspectors report that blue dust was blowing out of the facility at the time as well. At right, liquid runs off the wet cake storage area. (Photos by Jason Windhorst, NDEE)

Yet the larger question of how pesticide-treated seed is being disposed of by agrichemical companies has gone unanswered, even as an industry-government alliance focused on pesticide safety has convened a task force that includes representatives of the companies to probe disposal problems.

AltEn was one of two ethanol manufacturers accepting treated seed in the U.S., and the six companies and others all chose to send their excess seed there when it was operating. Now that both have shut down, it’s unclear how those companies are disposing of the same volume of waste seed, which is likely toxic when aggregated. So far, the task force has taken steps to provide resources to farmers for disposal of seed that goes unused on farms. But the companies have not disclosed anything about their own disposal practices for surplus, expired, returned or quality-compromised seeds, a potentially much larger volume of waste.

The companies’ detailed remediation plan for Mead outlines how they are treating wastewater to remove chemicals and containing the excess wet cake. It doesn’t mention, however, whether that hulking heap of seeds was still present when they took over the cleanup or if and how it has been cleaned up. Before adding seeds to the pile, AltEn was also storing a large volume in bags stacked on pallets in an adjacent building, according to inspection reports. The plan makes no mention of whether those seeds also remain on site and if so, how they might be disposed of.

A Bayer spokesperson who said she was relaying answers for the group of companies working on the cleanup said “we have no more detail to share” about how much seed was left on site or how it was disposed of. She referred Civil Eats to NDEE for additional questions. NDEE said it has no further information on the fate of the seed.

Planting Pesticides

During later site visits in 2020, Holsten, Pomajzl, and other inspectors focused their inquiries on the wet cake. One winter day, however, colleague Jason Windhorst looked toward the hoop building where AltEn housed the seed pile. Even from a distance, he later wrote, he could see that “blue dust is covering the ground, equipment, and parts of both buildings.” (Chemical-laced dust is known to drift off treated seeds during planting.)

Companies have not disclosed anything about their own disposal practices for surplus, expired, returned or quality-compromised seeds, a potentially much larger volume of waste.

Because of the direction of the light that morning, his camera couldn’t capture it, but he watched as the wind carried the blue powder out of the building and into the surrounding environment.

Seeds are elemental; human life depends on their power to transform into plants that produce nourishment. Seeds are sacred; shared and passed down over generations, they link Indigenous peoples and the African diaspora to lineages eviscerated by colonialists and offer opportunities for regeneration. And, for most of history, seeds were both the beginning and the end of a self-contained, unbroken life cycle: seed to plant to fruit to seed, over and over and over.

Now, in modern American agriculture, seeds may also be toxic waste.

Farmers and agrichemical companies have been treating some seeds with pesticides since at least the 1950s. However, the introduction of a class of insecticides called neonicotinoids combined with seed company consolidation caused a rapid scale-up of treated seed planting over the last 25 years. Today, nearly all of the corn seeds, the majority of soybean seeds, and many other crop seeds are coated with neonicotinoids, among other chemicals.

Called neonics for short, the insecticides become embedded in crop tissues as the plants grow, making them deadly to pests. But research shows the majority of the chemical coating leaches into the soil, where the insecticides persist in the environment and have devastating impacts on bees, wildlife, and—increasingly—mammals.

At very high levels of exposure, they can be poisonous to people. Some studies link exposure at low levels to developmental and neurological damage, but research on human health is still inconclusive. Public health experts have nevertheless urged the EPA to take steps to end their use, arguing that emerging research points to serious effects that haven’t been adequately studied yet. And studies show human exposure is widespread. Because seeds coated in neonics are now planted annually across hundreds of millions of acres, they are now detected in water and food.

Environmental groups have been fighting for stricter regulation of seeds coated with neonics for years, especially because the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), which regulates pesticides, doesn’t apply to treated seeds. The European Union has already banned the most common neonics because of their impacts to ecosystems. Lawmakers have proposed the U.S. follow suit several times, but the legislation has never become law.

“To date EPA has abdicated its legal responsibility to regulate the use and disposal of neonicotinoid coated seeds,” said Senator Cory Booker (D-New Jersey), who reintroduced a bill that would ban common neonics and make other sweeping changes to pesticide regulation in November 2021. “Seeds coated with neonicotinoids provide few benefits but many harms.”

On that 90-degree day in 2018, Holsten and Pomajzl put on hard hats, protective glasses, and gloves before taking samples of the wet cake. Later, various NDEE tests would show some of the material contained staggering levels of common neonics, according to public records. The Nebraska Department of Agriculture found clothianidin at a level that was 85 times higher than the maximum rates EPA deemed safe for field application.

As the saga has since played out, public records show the wet cake has been tested repeatedly and is now being consolidated and covered to contain the pesticide residues. But those materials were dangerous only because the ethanol process they came from started with neonic-treated seeds.

The federal law that governs waste disposal doesn’t apply if the seeds are being used to create another product like ethanol. If the seeds are simply being discarded as opposed to used in ethanol production, they would therefore be considered waste and be covered by the law. But the law does not address, specifically, whether they are considered hazardous waste when aggregated.

Instead, the law requires companies disposing of seeds to characterize whether the waste is hazardous and dispose of it accordingly. In addition, enforcement of hazardous waste regulations varies wildly from state to state.

An EPA spokesperson told Civil Eats that it does not track how treated seed is disposed of and that if the seed does qualify as hazardous waste, it “may be possible” to use a database they maintain for hazardous waste disposal to track it. Information in that database is, again, dependent on state laws. Despite the situation in Nebraska, the EPA says it “is not considering any new regulations specifically for the disposal of treated seeds.”

In a statement, Bayer said that it is common for seed companies to have “a portion of seed” become unstable and that, since the experience with AltEn, “we have conducted additional reviews and in-depth, on-site assessments to ensure well managed and compliant disposal of this product, and we are also examining ways internally we can reduce unusable treated seed volume on an ongoing basis.” The company declined to share any details on how it disposes of treated seed.

“We really need regulators to step in and to push the industry to be transparent about where excess treated seed is going and how it is being disposed of.”

AgReliant Genetics told Civil Eats its company’s specific procedures for handling unused seeds are confidential. “AgReliant Genetics has always worked closely with the industry and our customers to reinforce procedures for proper handling of treated seed at every stage of the seed’s life, and we continue to do so,” a spokesperson wrote in an email.

A spokesperson for WinField Solutions similarly said that company “is committed to safely discarding these seeds, adhering to local and federal rules and regulations, as well as our agreements with seed manufacturers.” WinField did not answer specific questions about how or where the seed is disposed of.

Neither Corteva nor Syngenta responded to detailed questions about their seed disposal practices. Beck’s also did not respond to a request for comment.

“Our concern is that [since] this concentrated situation has caused so much harm around Mead, disposal of treated seed is going to wind up being spread out in multiple locations across the country,” said Sarah Hoyle, a pesticide program specialist at the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Since the pesticides could seep into groundwater or drift into the air if seeds are discarded without special containment systems in place, she said, “That is why we really need regulators to step in and to push the industry to be transparent about where excess treated seed is going and how it is being disposed of.”

The Blame Game

In early February, as members of the Pesticide Stewardship Alliance (TPSA) gathered online for their annual conference, it looked like industry insiders were gearing up to talk about challenges with treated seed disposal and how they planned to meet them. The issue was on the agenda, and individuals representing all of the big players, including Bayer, Corteva Agriscience, and Syngenta, were in the virtual room. Agency officials from the EPA, California’s Department of Pesticide Regulation, and 20 different state agriculture departments also attended; some participated in presentations.

But when Bayer’s Darrel Armstrong appeared on the screen to talk about “BMPs (best management practices) for Treated Seed,” he began with the disclaimer that he couldn’t talk about how Bayer, specifically, disposes of treated seed. “These best management practices are really part of the considerations that we went through as an organization, but they’re not specific to Bayer and they don’t necessarily reflect all of the typical actions we would take internally,” he said.

The practices Armstrong then laid out relied heavily on instructions that have long been listed on EPA-approved labels on seed bags and a CropLife guide to “Seed Treatment Stewardship” that was released in 2013 and includes bullet points on disposal. The most common disposal options, he said, are burning seeds (at times producing power or other materials from that incineration), sending seeds to a properly permitted landfill, or ethanol production (which the industry still recommends if the byproducts are handled properly, even though the state of Nebraska has since banned it because of the contamination at AltEn). Farmers could also plant leftover seeds “in a fallow area in a field or double plant in a planted area” if the planting still complied with label instructions.

Armstrong said the biggest source of treated seed trash is “obsolete or quality-compromised seed.” Traditional seeds can be preserved for hundreds of years, though most lose their ability to germinate over time depending on storage conditions. Seeds coated with pesticides degrade faster; Armstrong said soybean seeds typically don’t last more than a year.

None of the companies Civil Eats contacted would share information about how much treated seed they dispose of each year. The Winfield United spokesperson said it discards a “very minimal amount.” Last year, however, anonymous industry sources told an ag industry publication that they’d estimate about 10 percent of the treated seed that farmers buy goes unused, which they calculated would mean millions of bushels discarded each year.

Industry experts told Civil Eats that, in some cases, farmers can return unused seed to their dealers, who may return it to the companies for disposal. And those numbers don’t account for seed that might have been overproduced by companies and never sold to farmers.

The bulk of the treated seed being sent to AltEn came from the agrichemical companies themselves, according to AltEn’s own advertising. Despite that, the companies appeared to be placing the responsibility for disposal onto farmers at the TPSA conference.

The day before Armstrong’s presentation, Jack Ranney and Clinton Shocklee, co-chairs of TPSA’s first “Treated Seed Task Force,” referred to the same CropLife guide Armstrong mentioned, calling it a crucial tool. Against a backdrop of corporate logos—Bayer, Syngenta, and Corteva Agriscience—they said the task force made up of lobbyists, government regulators, corporate representatives, and industry and academic experts had identified contacts at government agencies in 10 corn-producing states who could serve as resources for farmers on how to dispose of treated seed.

Though the task force was created as a direct result of the AltEn disaster, they talked exclusively about helping farmers dispose of treated seed properly. Both repeatedly congratulated the task force on its progress to date.

When asked why the Task Force focused on farmer disposal assistance, Ranney said in an email that the reason was “the ever-changing rules related to treated seed disposal.” Questions about how the agrichemical companies should dispose of the seed, “would be best directed to seed companies,” he added.

Publicly, agrichemical companies have highlighted AltEn’s alleged malfeasance in accounting for the contamination, and allegations laid out in lawsuits paint a picture of AltEn as a uniquely bad actor. For example, one lawsuit claims Tanner Shaw listed his address as a $30 million Kansas estate equipped with a scuba-diving pond and still allegedly abandoned the AltEn site, selling off assets to avoid financial responsibility for the contamination in Mead. (The estate, now sold, was built by his stepfather Dennis Langley, the company’s founder, an influential figure in the Democratic party who was once the chief speechwriter for then-Senator Joe Biden and made his fortune on natural gas pipelines.)

According to NDEE, for years AltEn regularly violated laws that were in place to prevent the environmental contamination that could result from making ethanol with treated seed. Bayer’s litigation charges “AltEn failed to properly handle, store, and otherwise manage the [seed] and the by-products from the ethanol manufacturing process in violation of federal and state laws and AltEn’s contractual commitments to Bayer.”

The litigation estimates Bayer has spent $1.5 million on the clean-up as of March 2 and, like the other lawsuits, claims AltEn abandoned the unstable facility a year ago. Syngenta’s complaint says that the six companies “stepped up to the plate and volunteered to address immediate risks at the site, although they had not caused the AltEn mess.”

Still, the larger questions about ongoing treated seed disposal remain.

In Mead, contractors are covering the wet cake pile with a hard shell, repairing wastewater lagoons, and treating the wastewater so it can be spread on fields. As for that rainbow volcano, without more information from NDEE or the companies overseeing the cleanup, its fate remains unclear.

In February 2021, Pomajzl and Holsten went back to the site to inspect the wet cake storage. This time, they didn’t enter the white hoop buildings used for seed storage. But from the outside, they once again noted that the blue dust from seed coatings was not staying put. “Discoloration of the white hoop buildings appeared to be more pronounced compared to previous site visits,” Holsten wrote. “In addition, some snow on the ground . . . was also discolored.”

As recently as January 2022, various NDEE inspectors found bags of rotting seed on the ground outside on multiple visits. An agency spokesperson said those bags have since been cleaned up. In February, an update sent to NDEE by the group of companies working on the cleanup did not mention the seeds. The group did say its team was “dealing with leftover chemical inventory” but the spokesperson for the group would not say whether that “chemical inventory” included the seeds. “Everything AltEn left on site when it ceased operations has been reported to the state and accounted for. We would refer you to the NDEE for that information, as we are fully focused on the future,” she wrote.

Hoyle, at the Xerces Society, is also thinking about the future. Getting rid of treated seeds could concentrate some of the risks associated with planting them, she said. For example, research shows contact with neonics can kill pollinators, harm aquatic invertebrates, and affect bird populations. The difference, she said, is concentration: neonic use across millions of acres is akin to exposing entire swaths of the country’s ecosystems to low-level chronic exposure, while disposal of tons of seeds in one place amounts to a massive dose, potentially leading to more acute harm.

What happened in Mead with honey bee colonies dying off and high levels of water contamination “are somewhat extreme examples of what’s going on on corn and soy fields around the country,” she said. “I think we need the industry and regulators to come together to find an appropriate disposal solution and also be transparent about where it’s going.”

This story is part of an ongoing Civil Eats investigation. Contact senior staff reporter Lisa Held with information about treated seed disposal at lisa@CivilEats.com or securely at lisaelaineh@protonmail.com. Ask her for her Signal info.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

People were advised to stop feeding and to disinfect the feeders.

I am just wondering : Could the seeds have been

toxic ??? If you have any related information, please let us readers know.

And THANK YOU all for your great work and reporting ,

Marianne