Federally funded agricultural gene banks work to safeguard crop diversity and provide seeds and cuttings for research, breeding, and education. But too many public requests are hindering their work.

Federally funded agricultural gene banks work to safeguard crop diversity and provide seeds and cuttings for research, breeding, and education. But too many public requests are hindering their work.

April 27, 2017

This year, in the six weeks spanning late winter and early spring, the U.S. gene bank that stores vital, sometimes rare, collections of fruit varieties received around 280 requests for cuttings. Like many farmers and gardeners looking for unique wine grape, plum, peach, persimmon, olive, and walnut trees, these savvy folks went straight to the source. But most of their requests were turned down.

“We approved only 50 of them,” said John Preece, research leader at the National Clonal Germplasm Repository based at University of California at Davis. “Our gene banks have become overwhelmed by orders from the hobbyists and home gardeners in recent years,” Preece added.

The mission of the U.S. gene bank system is to conserve the germplasm—the seeds or tissues that conserve crop genetics—and provide them for research, breeding, and education. The 19 U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) gene bank facilities located around the country, collectively, store 570,000 unique samples of 15,000 plant species that make up the National Plant Germplasm System (NPGS) (each facility safeguards different collections of regionally appropriate plants). It serves as the backbone of national efforts to safeguard food security and maintain the agricultural economy. Increasing requests from the public, however, are putting a strain on the system.

The bulk of filled requests come from plant breeders or researchers searching for specific crop traits of interest. Other requests come from farming or gardening associations interested in multiplying seed to distribute among their users. Increasingly, however, requests are coming from home gardeners. Some requestors can be rude—occasionally threatening—demanding access to seed as a taxpayer right. People who submit fraudulent requests deliberately misrepresent their intended use, often to simply secure free seed. There are even social media posts offering advice on how to word a request to get it filled.

Plant shoot tips are frozen within droplets of cryoprotection solutions on foil strips. The strips are plunged into liquid nitrogen slush that is formed by placing liquid nitrogen in a vacuum. (Photo courtesy of the USDA Agricultural Research Service.)

Plant shoot tips are frozen within droplets of cryoprotection solutions on foil strips. The strips are plunged into liquid nitrogen slush that is formed by placing liquid nitrogen in a vacuum. (Photo courtesy of the USDA Agricultural Research Service.)Annual demand for germplasm has doubled since 2005. The gene banks that house fruits and veggies are, not surprisingly, the top targets of public requests. “The percentage of requests that we [NPGS] really cannot fill overall has grown, system-wide, to roughly 30 to 50 percent of those received—which surprised me,” said Peter Bretting, the USDA-ARS senior national program leader for plant germplasm, based in Washington, D.C. “If we fill 7,000 requests, and there are another several thousand we process, review and make decisions on; it has a cost—namely the extensive use of personnel’s time.”

The High Costs of ‘Free’ Plant Requests

All those requests add up. “I would estimate the time required to handle this issue [at our gene bank] probably costs an equivalent of $100,000 annually in staff salary and benefits,” said Candice Gardner, research leader at the USDA-ARS North Central Plant Introduction Research Unit at Ames, Iowa, which banks 1,700 vegetable, oilseed, and ornamental samples and receives around one-third of the total requests.

“To me, the real cost is in the work we could be otherwise doing,” she said. The NPGS budget, currently around $40 million per year, to maintain viable seed for distribution hasn’t kept pace with increasing requests. Only limited quantities of each seed sample are available.

The spike in requests is due to a number of factors. Implemented in 2015, the GRIN Global database (an updated version of GRIN, the Germplasm Resource Information Network), is easier to query, says Kim Hummer, the research leader at the Corvallis, Oregon-based National Clonal Germplasm Repository, the gene bank that stores berries, pears, hazelnuts, and hops.

New food trends also spark interest in older varieties. For example, the cider-making craze catalyzed searches for vintage cultivars of pears. At the same time, Hummer says, research requests have spiked as well—for example, for disease-resistant strawberry varieties in California, since growers can no longer use methyl bromide there as a pesticide.

“While we have specific heritage-type material or wild species, we don’t have the latest, greatest new cultivars out there,” said Hummer. “Homeowners usually have a different need than what gene banks can fulfill in most cases,” she added.

Alternatives to Gene-Bank Requests

When individual requests are denied, Hummer and Preece point people to other groups or local nurseries and garden centers, which can usually provide appropriate plants for homeowners. Not long ago, in fact, Preece explained to members of the California Rare Fruit Growers, an amateur fruit-growing organization, that he can no longer accept individual orders. He did, however, agree to fill one big order for the organization—up to 25 items each year—which they can propagate and exchange among the group.

Technician April Stanley retrieves specimens from a liquid-nitrogen freezer. (Photo courtesy of the USDA Agricultural Research Service.)

Technician April Stanley retrieves specimens from a liquid-nitrogen freezer. (Photo courtesy of the USDA Agricultural Research Service.)A number of online tools—including PickACarrot.com or the University of Minnesota’s Plant Information Online directory—exist to help interested parties locate sellers of heirloom or unusual cultivar seeds.

Luckily, however, the number of seed sources is also on the rise to help meet the growing demand. Arizona-based Native Seeds/SEARCH is one of the most visible in the greater Southwest. “We have had a pretty consistent increase in the demand for our seeds,” explained Native Seeds’ conservation program manager Nicholas Garber. “We have had a considerable expansion in our programs, offering seed in larger quantities to small farmers, likely due to the increased demand for heirloom varieties in food markets.”

Graber recommends that people interested in locally appropriate seeds learn to grow and save seeds themselves, and familiarize themselves with seed libraries. In the last five years, up to 500 seed libraries have been founded around the U.S.

Likewise, organizations like the Rocky Mountain Seed Alliance, based in Ketchum, Idaho, serve as venues to trial, identify, and propagate seed that will grow in the region. “We’re doing the research to find which grains work for our region,” said director Bill McDorman.

A few years ago, he conducted a nationwide search of grains that might grow well in the Rocky Mountain West. The seed he requested via GRIN, combined with that from other Rocky Mountain seed stewards, totaled roughly 100 varieties, which are now part of their Heritage Grain Trials program. “We’re increasing those seed so other gardeners have access to them,” said McDorman. So far, he says, they have around 35 people signed up to grow out small samples so that farmers can receive 20-pound bags of seed in a couple of years.

McDorman thinks the explosion in local food is now evolving into greater awareness about the use of locally adapted seed. The way he sees it, the NPGS conserves the seed so that organizations like his are able to field trial varieties to re-adapt varieties to, for example, changing climate conditions.

“We’re really excited to see people interested in the plant materials that we strive to preserve for all people for all time—it’s a grandiose long-term view of conservation that we are dedicated to,” said Hummer.

Gene bank staff want to be loved, says Preece. Just not loved to death.

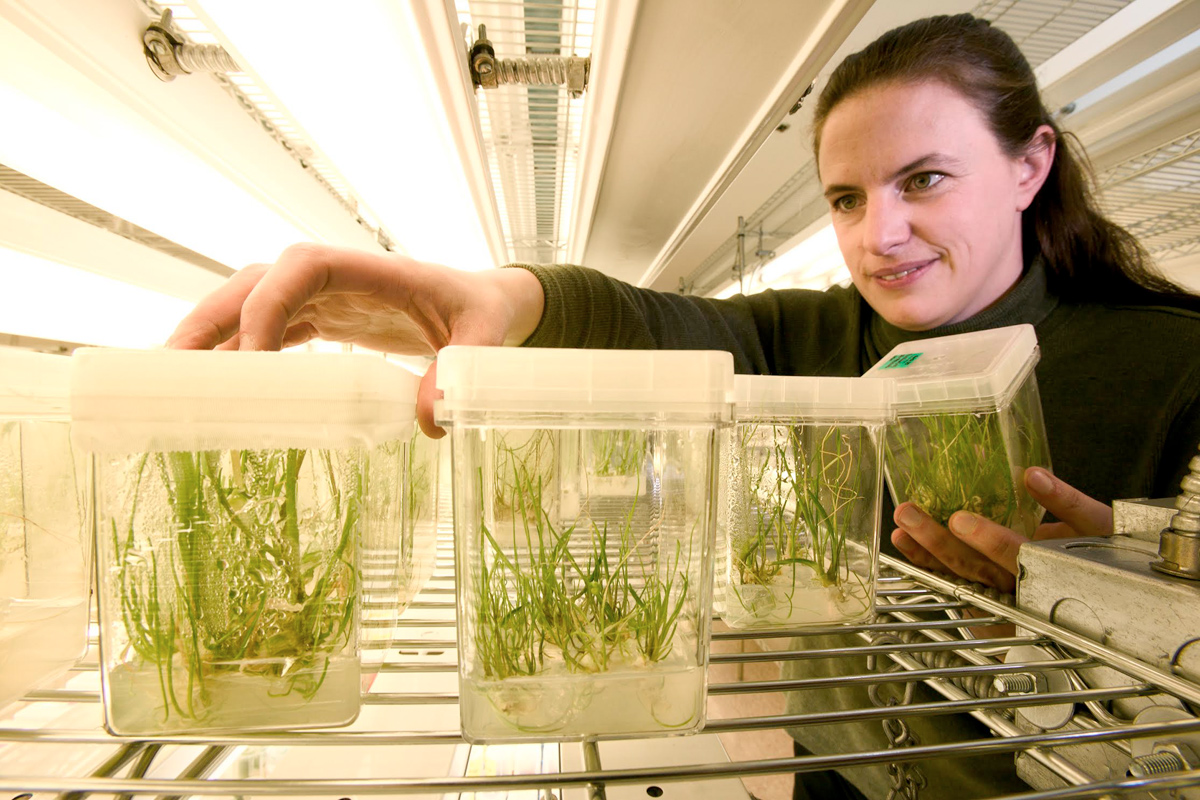

Top photo: Plant physiologist Gayle Volk inspects garlic plants growing in culture. Shoot tips of garlics were cryopreserved because these plants represent the greatest genetic diversity in the collection. (Photo courtesy of the USDA Agricultural Research Service.)

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

Lately I have been getting requests from others that the USDA has sent my way (some of the material was removed from the system or put into storage at Fort Collins, Co.). If someone is breeding or doing seed increases and I still have viable seed, I am usually glad to help.

That may be one alternative but still takes conservators time to look up records or maintain some sort of tracking system.

In the above situation, people in government tax others (ie, take their money under the threat of locking them in a government cage) and give it to researchers and administrators.

"Gene bank staff want to be loved", quotes the article. But do they deserve the love of people whose stolen money they take?

Someone who forces their wants on another, threatening them with violence and imprisonment should they not comply, may also claim to want the person's love.

But they do not deserve, and will never receive it.

In the above situation, people in government tax others (ie, take their money under the threat of locking them in a government cage) and give it to researchers and administrators.

"Gene bank staff want to be loved", quotes the article. But do they deserve the love of people whose stolen money they take?

Someone who forces their wants on another, threatensing them with violence and imprisonment should they not comply, may also claim to want the person's love.

But they do not deserve, and will not receive it.

Though I fully realize that the NCGR is underfunded and there are too many hobbyists requesting genetics, this is not the way to go about distributing germplasm. In cancelling everyone without a .edu/.gov/.org email address and then making them show letterhead proof of institutional backing, you are discriminating against the self employed and unfunded farmers/breeders/researchers conducting valuable research that props up university research. There needs to be another way. A longer application, perhaps that vets people in other ways than their institutional affiliation.