The author of ‘Sweet In Tooth And Claw’ challenges the notion that humans are meant to dominate and control their environment, and invites readers to see themselves as partners with nature instead.

The author of ‘Sweet In Tooth And Claw’ challenges the notion that humans are meant to dominate and control their environment, and invites readers to see themselves as partners with nature instead.

January 11, 2023

Much thinking about the natural world is shaped by neo-Darwinism, an assumed struggle for survival on a planet where humans prevail over other species. But what if humans are not simply the apex predator, selfishly driven to devour the environment, destroy habitats, and dominate other creatures? What if they are instead the ultimate cooperators, ensconced in a system of mutually beneficial relationships, wielders of a unique power to uplift the natural world?

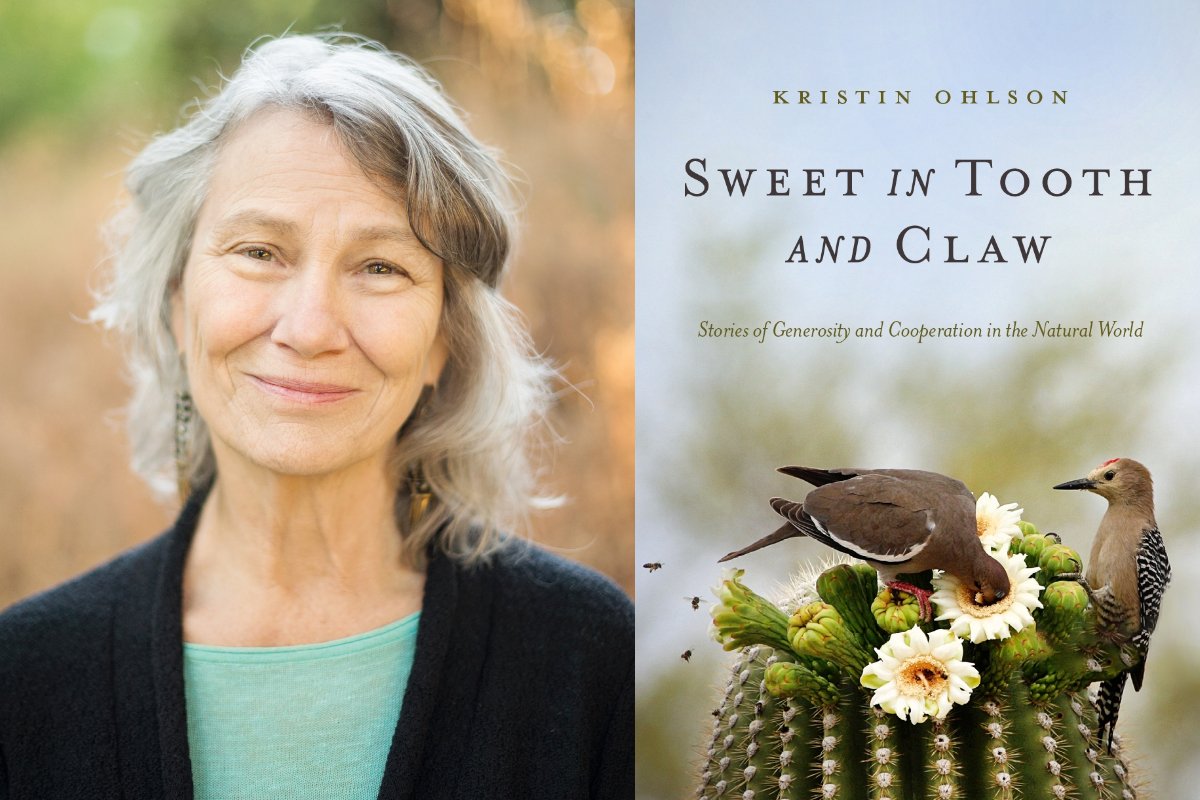

In Sweet In Tooth And Claw, author Kristin Ohlson explores cooperative relationships found in nature, from the evolution of the multicellular creatures that form the building blocks of all life to relationships between co-evolving plants and insects and their intersection with humans.

Ohlson is an Oregon-based writer whose last book, The Soil Will Save Us, became a bestseller that popularized the notion of improved soil management as a climate solution. She later appeared in the similarly themed, award-winning documentary Kiss the Ground. With Sweet In Tooth and Claw, she challenges the notion that humans are meant to dominate and control their environmental, and invites readers to reimagine them as key collaborators instead.

With expansive thinking and in relatable prose, she tours mutualistic experiments like a Nevada rangeland reinvigorated by beavers and a Mexican coffee plantation shaded by bird habitat, explaining research that makes a case for more such invention. Civil Eats recently sat down with Ohlson to discuss the book, and what she learned is possible when people see themselves as integral parts of the ecosystems in which they live.

There’s a great passage in your book about humanity’s narrative of itself. It’s about how metaphors of constant struggle and greed have become a dark lens that cause people see humans as the apex predator of the planet, and life as “a zero-sum game in which a benefit for one is a loss for another.” Are we the apex predator?

We have the ability to be the apex predator. I was just reading another author the other day who made the point that other creatures, especially big fauna, exist because we let them. We could so easily wipe them out. But if we unleash that power—and we certainly do way too often—it leaves us with a world in which the biology around us just dies off bit by bit. We are biological creatures. We’re not something that came out of a box on a factory shelf. If we did survive in a world where all the rest of the biology was denuded, I don’t think it would be the world we want.

Your book posits that humans are part of mutualistic relationships that sustain species through cooperation. Can you explain what a mutualism is?

A mutualism is a mutually beneficial relationship among two or more species. One that most people encounter every day, at least the one that we’re aware of, is that between pollinators and plants. But mutualisms go on constantly in every ecosystem. Scientists will say probably every living thing on earth engages in a mutualism—they can’t say all because they haven’t tested every single one. But I think it’s probably fair to say that there is no organism that doesn’t have some kind of mutualism going.

“We have the ability to be the apex predator. We could so easily wipe [other creatures] out. But if we unleash that power—and we certainly do way too often—it leaves us with a world in which the biology around us just dies off bit by bit. . . . I don’t think it would be the world we want.”

We have thousands, millions, of mutualisms with all those things that live in us and on us. Everything around us is engaged with everything else constantly, both in ways that we’re aware of, like with bees and flowers, and in ways that we’re not aware of, like what’s happening underground with the roots of plants and how they interact with fungi and bacteria and protozoa and small animals in the ground. It’s going on constantly right underneath our feet.

Can you give some examples of mutualistic relationships that humans have?

Well, there’s everything that lives in our gut—bacteria. And also things that live on our skin. And—this is somewhat different—but humans also have mutualistic relationships with each other. That’s what a city is. A city is a vast expanse of people doing different things that help other people survive.

It makes a big difference if we carry this idea around in our heads that all life is competition and conflict instead of held together by cooperation from the basic cells up. All the cells that we are composed of, those single-celled organisms, came into existence about 3.8 billion years ago. They sort of floated around in this world until around 1.8 billion years ago, when a new kind of cell formed. Then one swallowed the other, and it created a more internally complex organism. It’s called a eukaryote.

All humans, all animals, all plants, all fungi are made of these eukaryotic cells. They have the internal complexity that form relationships with other cells. That act of cooperation and connection is at the basis of all multicellular life. I think that’s a big deal.

How long have scientists known about mutualisms?

The first one that I know of would be in 1886. That was the Dutch microbiologists Martinus Beijerinck. He found that on the roots of certain plants, nodules formed that bacteria live inside and they are fixing atmospheric nitrogen. Basically, they are turning it into fertilizer.

If we were to take what’s been learned about mutualisms and redevelop policy around it, how would agriculture be different?

I think things really are changing a lot. Some of the things that the Biden Administration is considering is exciting stuff. At least the ideas are floating around. But we really could take these ideas and go with them.

If we did, you would never drive down a highway and see miles and miles of bare soil that sits out there for six months a year waiting to be planned for spring. It damages the life in the soil. You would always see a winter cover crop over that.

And what some of the most innovative farmers are now doing is having a couple of crops in the same field or having a cover crop that is also a market crop. They’re using their animals in those fields. All of that would look so much different. Visually, it would be a completely different look.

I’m always fascinated when I’m flying someplace and look down and see the dramatic engineering of the landscape because of modern agriculture. When you see those circles, it’s because there’s an irrigation pivot in the middle. If farmers were using cover crops, they would need so much less water because they wouldn’t lose so much of it to evaporation. We wouldn’t see naked soil like that anymore.

Can you talk about an example of innovation that’s more mutualistic?

One coffee plantation and the farm in Costa Rica is an example of how incredible a place can be when maximizing production is not the only goal. The goal of that coffee plantation is both to raise coffee and also to have habitat that birds flourish in.

“What some of the most innovative farmers are now doing is having a couple of crops in the same field or having a cover crop that is also a market crop. They’re using their animals in those fields. All of that [makes agriculture] look so much different.”

Coffee is an understory plant. That’s how it was first discovered in Africa. For years and years, it was grown in the shade. Then, because of the threat of rust, which is a fungal pest, the U.S. and some of the big agricultural companies pushed coffee growers to grow coffee in a monoculture in the bright sun and lose the services of all those other plants. This way, they would lose the shading services and the services of insects that would live in more varied plantations. And instead, they would have to deploy a lot of chemicals and lot more water. But the idea was that they wouldn’t get rust as easily. I don’t think that has proven to be true.

On the plantation that I visited, scientists are documenting all the relationships among all the different insects and fungi and things that live in that varied plantation. There are not only many varieties of shade trees that coffee grow under and around, but all these other trees that owners planted there to try to feed birds. People who aren’t planting in that way have to take care of those pests some way. There, the birds are taking care of it. And the really intricate dynamics, even between different fungal species, also take care of pests.

Did you talk with producers and growers about the barriers to engaging in this type of system? What is it that stops people from farming this way?

There are a bunch of things that stop people from ranching or raising crops or having orchards in a regenerative way. One of the main things is one of the most surprising things: It’s what their neighbors think.

A regenerative farm looks “messy.” There’s all this stuff growing between market crop, and they’re not spraying their edges to kill off weeds. If they’re really smart—and they are really smart—they’re letting stands of wildflowers grow so that birds and insects come in. And it doesn’t have that neat-as-a-pin look.

In these small farming communities, not only do their neighbors talk, but their bankers talk, their landowners talk. An awful lot of farmers are renting land from landowners who live out of town or maybe live in town and don’t understand why their farm looks so messy. That’s really a big thing—the expectation of what it’s supposed to look like.

It’s very difficult, given our farm policy, for farmers to be creative and not just do the cookie-cutter approach to farming that suggests heavy tillage, heavy chemical use, and high-tech seed use. They’re all getting loans at the beginning of every farming season, and it’s hard to convince a banker to support you if you are doing something that’s different and creative. It’s hard to get crop insurance if you’re doing something different and creative. And bankers don’t want to give loans to people who aren’t getting crop insurance.

“It’s very difficult, given our farm policy, for farmers to be creative and not just do the cookie-cutter approach to farming that suggests heavy tillage, heavy chemical use, and high-tech seed use. . . . It’s hard to convince a banker to support you if you are doing something that’s different and creative.”

Also, most of our ag education system is following that industrial-ag paradigm of heavy tillage, heavy chemical use, and high-tech seed use. For farmers who want to do it differently, where is the lesson plan? Where are the examples? Examples proliferate in YouTube videos—it’s not that it doesn’t exist anywhere—but it pales in comparison. The teaching and support for people doing regenerative agriculture is just a fraction of the support and education of people doing it the industrial way.

Regenerative ag is not a concept that the USDA has always embraced. In fact, there was a period where they were kind of against it. Can you give us some background on that? And is it changing?

We can all be so hidebound. Nobody wants to change, especially when you’re part of a huge bureaucracy. And I think especially when big government agencies like the USDA have to answer to politicians who answer to big funders. There was a lot of foot-dragging in the USDA and there still is, I imagine, around such questions as GMOs and chemicals in farming.

But it really is changing. When my soil book first came out [in 2014], one of the first people I heard from was a guy who was in the media department for the Natural Resources Conservation Service. They had this whole movement around soil, a huge push. They were really trying to convince farmers around the country to stop tilling and to use cover crops. And I think they probably would have loved to have told them not to use chemicals or to use fewer of them, but that was a tougher thing to get away with given the bureaucracy.

Scientist Jonathan Lundgren was operating within that bureaucracy at that time, working with soy and corn. He is an entomologist so he is really interested in finding natural ways that farmers could fight against the pests that plague crops. A lot of his research was showing that these miracle chemicals that the chemical companies were trying to sell to farmers, that would take care of this pest and that pest, they weren’t really helping at all. That’s when he really had his difficulties with the USDA and left.

Can you talk a little more about Jonathan Lundgren’s efforts to support new ways of farming?

He’s doing a lot of science, a lot of study, comparing regenerative farms and conventional farms and seeing really who is doing better. That one paper that he published right as I was writing this book compared conventional farms to regenerative farms and looked to see who is doing better. And it was the regenerative farms.

Their yields were not as high, but they weren’t spending tons of money on chemicals. And they were able to stack enterprises. So they had crops going, and when those crops were done, their animals would come through and eat the residue. This meant they had meat to sell from the same piece of land that another farmer would only be able to sell his corn or his soy from.

What was your takeaway after learning all of this?

If we have this idea that everything is competition and conflict, and that’s our guiding metaphor for what life is like, then we’re really missing the bigger part of the story, which is that life has been formed and is held together by these cooperative relationships, these mutualisms.

So when we look at a city—I had my window broken out yesterday. If we have this view of the world that everything is competition and conflict, well there’s just another sign of it. But if we have the view that really cities are these vast cooperative structures, but then stuff screws up every now and then, it’s a different view. It’s more fixable; it’s more workable. We are less likely to throw up our hands in despair if we think of it as we’re one of the most cooperative species that’s ever been.

Israeli author Yuval Noah Harari is among those who’ve said that humans are massively cooperative, and that is why we’re so deadly. We can organize ourselves around great causes. And sometimes the great cause is a really terrible one, like the Nazis.

But on the other hand, we can make the case that we can organize this very cooperative species around another great cause, which is repairing our relationship with the rest of nature. What excites me is that when people do figure out how we have been causing damage, and how we can pull back that damage, the rest of nature responds so quickly. Things regenerate in really powerful and unexpected ways.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 25, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.