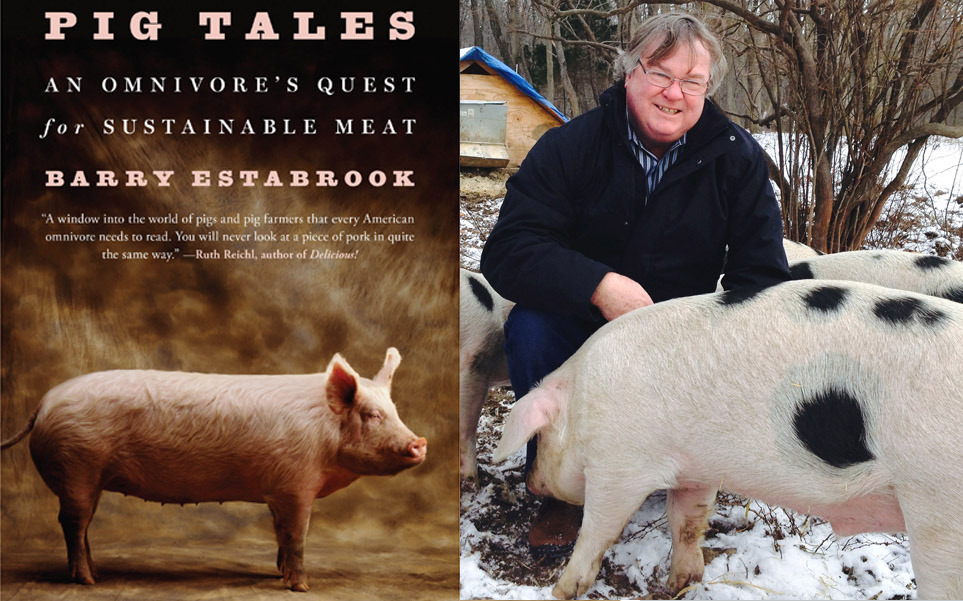

In his important new book, journalist and author Barry Estabrook talks about pig intelligence, Danish farms, antibiotic misuse, and today's meatpacking towns.

In his important new book, journalist and author Barry Estabrook talks about pig intelligence, Danish farms, antibiotic misuse, and today's meatpacking towns.

May 5, 2015

Not every writer can speak to both seasoned experts and curious newcomers, but that is precisely what Barry Estabrook can do well. In his 2011 book, Tomatoland, Estabrook took a deep dive in the modern tomato industry, shining a light on labor abuse in Florida, and the work of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers. In addition to telling a riveting and complex story full of pesticides poisoning, escape from slavery, and tense court cases, Estabrook helped bring attention to one of the most important American labor struggles of the last few decades.

With his new book, Pig Tales, Estabrook takes a good, long look at American pork production, telling a new set of fascinating, detailed stories about farms, communities, and the many haunting repercussions of industrial farming. He suits up and goes inside huge pork production facilities in the U.S. and Denmark, meets with animal welfare expert Temple Grandin, and walks through pastures with Paul Willis from Niman Ranch. The result is a thorough and alarming look at the path our pork takes from farm to fork.

We spoke to Estabrook about the research he did, the implications of what he found, and what everyday eaters can do to make a difference.

Do you want to start by talking about what you learned about the pigs?

One of the first things that surprised me was just how incredibly intelligent, and sensitive, and curious pigs are. Research at the University of Cambridge showed that they are as intelligent as 3-year-old children. I spoke to a scientist at the University of Pennsylvania who had taught pigs how to play a rudimentary computer game–and they did pretty well at it. Pigs can also watch other pigs and predict their actions, which was something scientists once thought was reserved for humans and the great apes.

They are incredibly sentient and aware animals. Then I got to thinking: when you take something this smart and this curious, and you pack it into space where it has no room to really move, or express any of its natural instincts, it becomes positively frightening. These animals are way smarter than the average dog or cat, and yet if someone treated a dog or cat that way, they’d be put in jail.

I was interested in what Temple Grandin told you about how giving a pig a small ball of straw can change their behavior radically.

Normally, a pig spends 75 percent of its waking hours rooting. So something as simple as throwing a softball-sized fist full of straw into a pen containing a couple of dozen growing pigs satisfies their minds, and it makes a remarkable difference in how they grow and how they act. The pigs don’t eat the straw, they just nuzzle it and bat it back and forth. It’s such a tiny thing and yet we don’t do that with our pigs here in the U.S. But they are required to give pigs straw in Denmark.

You dedicate a whole chapter to your visit to a large pork operation in Denmark. What was the biggest take-away from that experience?

Denmark’s pork industry is every bit as concentrated, modern, and sophisticated as ours. These are not wood-thatched houses with a couple of pigs running around. Their pork competes on the world market against ours. Yet they’ve made several small, but very important changes in the way they produce it. For one they don’t keep their sows in gestation crates. Three quarters of our sows spend their entire lives in crates that are actually too small to accommodate their bodies. In Denmark, the pregnant females are kept in larger stalls with a couple of dozen other females, and they don’t seem to have any problem at all.

More important, they don’t use antibiotics for growth promotion at all in Denmark. And when they do use antibiotics it’s very strictly limited to cure disease. Producers here claim they can’t raise pork without feeding the animals constant low doses of antibiotics.

The fact that the Danish farmers were so involved in setting and maintaining standards around antibiotics use for one another was especially interesting. They actually hold each other accountable.

It’s Scandinavia, so all the farmers belong to a giant cooperative, which owns the slaughterhouse, etc., and that changes the whole dynamic. They’re not contracting for a giant company. And 15 years ago they decided there was going to be a problem with antibiotic resistant bacteria if they kept using antibiotics in the way they were. And they all made the change together. That gave no one an advantage over the next farmer.

A great deal of the book focuses on large facilities, and you have a short section on small-scale, pasture-based farms. Is there a future for mid-scale meat production in this country?

Niman Ranch functions like a mid-scale operation. It is not a ranch, despite it’s name. It’s a marketing company that sells pork from around 500 mostly modest-sized family farms. That model is working. It gives the farmers more money, and the meat is available nationally.

I also feature a group called the Ozark Mountain Pork Cooperative. They’re a cooperative, rather than a marketing organization, and their farms are usually twice the size of the average Niman farm. These are mostly former confinement farmers, who have changed their practices, and they’ve been successful marketing their meat through Whole Foods and Chipotle.

If you look back a few decades, we are raising the same number of pigs at any given point as we were in the 1970s. But two things have changed. Confined pigs grow a lot faster, so we produce more per year. Pigs are also now kept in larger and larger concentrations. In North Carolina, for instance, the average pig herd went from less that 200 in the 1980s, to several thousand today.

You write about the people who live near or around large-scale pig farms. Most deal with liquid manure in the air, on the ground, in the water–to the point where they cannot spend time outside. Tell us about them.

I talked to two very different demographics. One was made up of poor African Americans living in North Carolina. There have been many multiple studies and surveys showing that hog farmers place their operations in areas that are predominantly poor and black. Once that happens, these people don’t have any choice. Their houses tend to be fairly insubstantial–small frame houses or mobile homes–so they’re not worth much in the best of times, but certainly not when there’s a hog farm down the road. So those people are left to suffer along.

In Missouri, I spent time with another group of farmers. They were more well-to-do, had been on the land for generations, and were far from helpless. When they were confronted with hog operations moving in, they hired lawyers and sued the company under the nuisance laws. And they kept suing this big corporate farm called Premium Standard (which has since been bought by Smithfield, which was then sold to a Chinese company called Shuanghui in 2013) and they won five out of six lawsuits. The company would fight the lawsuit, pay millions in settlements, and then continue to [spray raw manure near the plaintiffs’ homes]. To this day they haven’t stopped. Despite paying out millions of dollars, the stink is still there.

One lawyer told me that he’s found out that [Premium Standard/Smithfield] had simply budgeted the lawsuits into the cost of production. We’re talking tens if not hundred of millions of dollars. So when you go and buy a $3 dollar industrial pork chop, a portion of that goes to pay lawyers.

You wrote: “Whether we like it or not, we’re all part of a huge international experiment on the effects of sub-therapeutic antibiotics.” What role does pork production play in that experiment?

About four out of five pigs are raised on a fairly steady diet of low-level antibiotics. Research shows that not only do antibiotic resistant bacteria develop on pig farms in this country, but that people who work on the farms (and some people who don’t) pick it up somehow. These resistant bugs can travel on the air, in the water, and they can contaminate meat that you get in the grocery store. That’s the experiment we’re running.

I wrote about a woman named Everly Macario who lost her 18-month-old son to an illness caused by resistant bacteria of some kind. It was horrific. The boy had never even been close to a farm, but the type of bug that he caught is the type that probably did evolve on a farm.

When you get a cut, or when you pick up a urinary tract infection, or some sort of sore throat, does it ever cross your mind that you might die? Before the advent of antibiotics, that would have been your first worry. Antibiotics have done that much for us and we’re squandering them.

And the FDA’s voluntary control program on farms is a farce. Because antibiotic use is soaring in farm animals. Most of the antibiotics farmers use here are for growth promotion, but the Danish farms don’t have a problem with growth. They’ve changed the rations and they’ve worked a lot on breeding. Their pigs are growing fine. A study done in Iowa found that it would cost about $4.50 per pig to do the same thing here in the U.S.

How did the time you spent interviewing workers in the meatpacking town of Milan, Missouri expand on what you’d learned about food labor in the Florida tomato industry?

There were lots of echoes. The labor abuses in the packing industry don’t approach what was going on in Florida when I first went there, and the workers at the packing plants do make about $12-$13 hour, but many things that were the same.

The conditions in Florida has improved dramatically since I wrote Tomatoland. Workers are making more money, they have more protections, and there are fewer reports of serious abuses, such as slavery or sexual predation. The trend is going in just the opposite direction in meatpacking. The wages have dropped by 40 percent. Meat packing used to be no more dangerous than your average industrial job, but it has become much more dangerous. And studies show that the people most likely to get hurt are Hispanic.

When they set up that plant in Milan, the citizens thought, “Great. Good jobs for our men and women.” But guess what? No Americans wanted those jobs. So this little town of 2,000 people has become more than half Hispanic in the last decade.

More people are immigrating to towns like Milan, instead of moving to big cities. And meat packing has been a driving force, hasn’t it?

The meat packing corporations decided in the 1980s to move away from urban areas, into rural areas, partially because that’s where the meat is. But also, that’s where the unions are not. They’ve created this situations and then they’ve created the type of very physically demanding jobs that only appeal to immigrants who are quite desperate.

I spoke with a woman who had been a good employee at the plant for 13 years. Then basically her wrists fell apart, her shoulders fell apart, and her hands became like claws. So then the company–she says–kept giving her nastier and nastier jobs to get her to quit.

How can consumers avoid meat raised (and processed) in the ways you’ve described?

Ten years ago it was much harder to find pork that was raised humanely, on pasture. You had to raise it yourself, or know someone personally. But it’s getting easier to find. I came to the conclusion that pork is either the best meat–from the perspective of the environment, animal welfare, labor justice, etc.–or the worst. Many of us have a choice. And consumer demand can drive change. Gestation crates for sows are going to be gone in the next 10 years. And that’s because large retailers picked up on consumer demand and said, “we’re not going to buy this stuff.”

Congresswoman Louise Slaughter (D-New York) also introduces a bill to ban sub-therapeutic use of antibiotics on farms every year that is slowly gaining support. But it’s going to take a lot overcome the power of Big Pharma and Big Ag. Policy change could make a big difference, but I don’ think we should dismiss what individuals can do themselves.

October 9, 2024

In this week’s Field Report, MAHA lands on Capitol Hill, climate-friendly farm funding, and more.

October 2, 2024

October 2, 2024

October 1, 2024

September 30, 2024

September 25, 2024

September 24, 2024

Like the story?

Join the conversation.